longboarders find their version of the perfect wave in the curves of high-end suburban decay

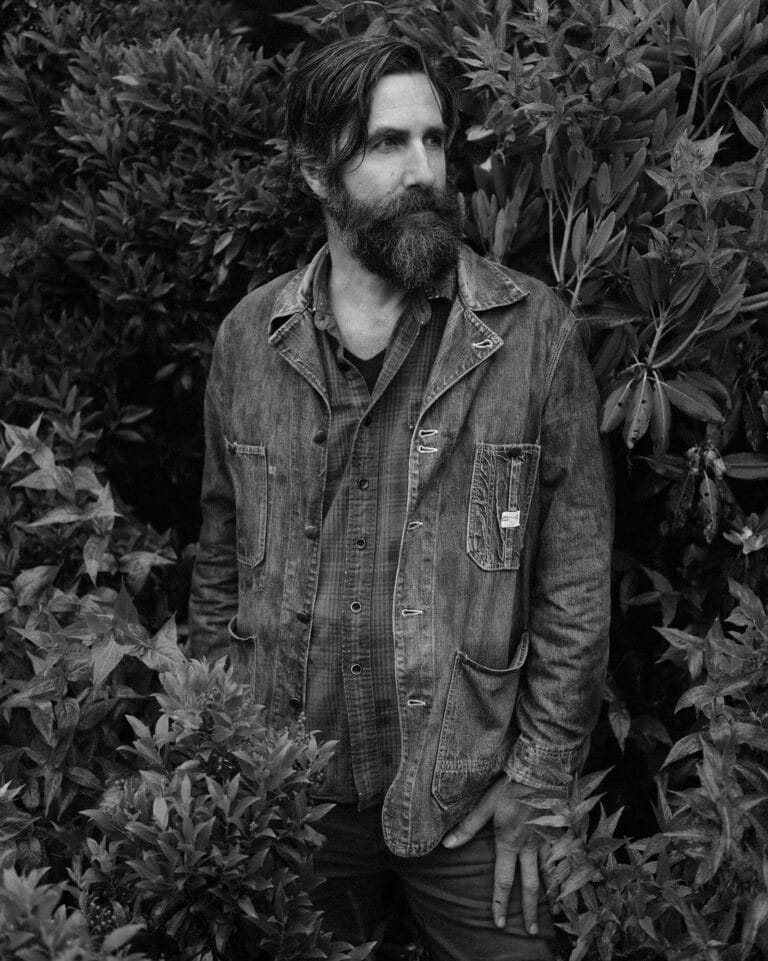

Philip Aschliman knows a few good roads for longboarding. The one we’re standing beside is two minutes from downtown Asheville. It has no potholes and offers a consistent slope. The straightaways run about 50 yards before bending into two gorgeous 170-degree switchbacks that seem right out of a Porsche ad. It’s a perfect setup. Well, almost.

With me as his spotter, watching for traffic at a three-way intersection at the bottom, we wait for a chance when no vehicles are coming. Taking off down the straight, he carves long esses to regulate his speed. Aschliman approaches the turn wide, crouches deep, drags one gloved hand on the asphalt, and starts an intentional drift—sliding as he aims for the turn’s apex. The run is an exciting negotiation of speed, balance, and traction up until the moment I call him off. There’s a U-Haul truck creeping up the hill.

Somehow motorists have cultivated the idea that they should be allowed access to this majestic piece of asphalt, too.

That’s always been the case for skateboarders. Their sport has always been at odds with the general public and the original intended use of good skateboarding terrains. And while street skaters have convinced many municipalities to build skate parks, downhill riders still have to fend for themselves in traffic.

That’s always been the case for skateboarders. Their sport has always been at odds with the general public and the original intended use of good skateboarding terrains. And while street skaters have convinced many municipalities to build skate parks, downhill riders still have to fend for themselves in traffic.

But Aschliman and many Southeast longboarders have discovered the closest equivalent to their niche’s version of a perfectly sculpted bowl in the form of a multitude of now-bankrupt high-end neighborhoods that dot the Appalachians. Yes, many of the mountain developments that once promised seclusion and long views—but barely got past the roadbuilding phase before swirling down the financial toilet bowl—have now become home to skateboarders.

“It’s easy to find these places,” says Aschilman, who hosts a group on Facebook that meets for regular rides in his area. “I just go onto Google Earth and start searching around. Look for that telltale brown spot where all the trees have been freshly cut down around a neighborhood road.” It doesn’t hurt to type “development + bankrupt + (town name)” into a search engine, either.

He’s disgusted with the way the land has been treated, but he can’t resist the chance to have these places to himself. For longboarders, “these defunct neighborhoods are an opportunity similar to the California drought in the 1970s that started vert skating in empty swimming pools,” he says.

With a little GPS work, he and his friends have become suburban explorers, scouting and riding unused and secluded neighborhoods that were named after the mountains they’ve scarred, the trees that were cut down in their creation, and sometimes famous naturalists—ironically titled reminders of the natural habitats they graded over.

“Last weekend, we went to a neighborhood that I had just found, and it was completely deserted,” he says. “There wasn’t a single house, and everything was overgrown.” The place looked deserted, but that’s an impossible claim since it never had inhabitants in the first place. He strongly warns against riding a road like that by yourself, noting that if you wipe out hard, it could be days before anyone finds you.

Before riding, longboarders will often walk the road with a pushbroom to clear away debris like gravel, acorns, broken bottles, and dirt patches that could send them sailing. “And we always keep a lookout posted near the road’s entryway to stop cars if they try pulling in.”

Once it’s all clear, the longboarders are free to carve and glide their way from top to bottom. The only downside to these streets, is that they are all still steamroller-smooth. This offers better traction, making it harder to tailslide. That’s where the gloves come into play. They’re usually made from gardening gloves that have Corian, Delrin, or UHMW hard-plastic pucks velcroed to their palms. They allow the rider to lean into the turn harder than normal, bracing their weight onto their hands as they drag across the asphalt. The puck is slick enough that it won’t grab the road with any force. Good gloves are available online for between $40 and $100, but many riders opt to go the DIY route.

Aschliman has taught many friends to ride hills like this, and he often meets up with riders who drive up from the coast just to carve a piece of the Blue Ridge roadways away from traffic. But the one piece of knowledge he won’t give away is the locations of where he rides. Technically, riding skateboards on streets is often illegal, and he is careful not to over-ride or over-hype certain roads as it will attract law enforcement—which (along with guardrails) are the longboarders’ natural enemy.

So he keeps his spots hush-hush. But he encourages other interested skaters to bring their safety gear, learn at a safe pace, be respectful to people who might live nearby, and go find a vacant neighborhood of their own. •