The public comment deadline on the proposed spaceport has been extended to March 8. You can learn more at wildcumberland.org.

A commercial rocket facility would regularly close a national seashore to the public.

“What other national park in America faces the prospect of fiery destruction every month?” asks Rebecca Lang. She is part of a community next to Georgia’s Cumberland Island National Seashore and in the flight path of a proposed commercial launch facility on the adjacent mainland. If the facility is built and rockets are launched, Cumberland Island could be frequently closed to the public, sometimes for days or weeks at a time.

And at least 20 percent of the rockets launched each year would be expected to fail, resulting in explosions and debris raining down on the island.

No other national park is closed to the public to accommodate a private enterprise.

“No one would close the Smokies or Yellowstone or any Wilderness area to the public so that a private company can engage in business over it,” says Carol Ruckdeschel, a celebrated sea turtle biologist on Cumberland Island. “A taxpayer-funded, publicly owned national park should not be closed to accommodate a private company, especially one that would threaten the health and safety of visitors.”

The commercial rocket facility is being proposed by the leaders of rural Camden County in south Georgia, and they have already spent $10 million in taxpayer money trying to get it approved. In 2018, Camden County withdrew their first proposal just before it was likely to be rejected by the FAA for failing to satisfy safety requirements.

Camden County filed a scaled-back proposal earlier this year, and in the meantime, they also quietly granted themselves emergency powers to evacuate Cumberland Island and nearby residences whenever they deem necessary for the commercial interest of the rocket facility.

“The emergency powers amendment seems to allow the commission to declare an emergency prior to a rocket launch and then use police powers to pull people out of their homes,” says Kevin Lang, Rebecca’s spouse and a Georgia attorney.

The proposed site is only a few miles from the country’s largest nuclear submarine base, which has raised concerns from the U.S. Navy. The National Park Service has also expressed alarm about the proposed rocket facility. Former national seashore superintendent Fred Boyles called it “one of the greatest existential threats that Cumberland Island has faced.”

The site has already experienced deadly explosions before. In 1971, an industrial fire and explosion killed 29 and injured 50, with shock waves shattering windows up to 11 miles away. The site was owned by Morton Thiokol, Inc., which manufactured booster rockets on the site for NASA. Union Carbide purchased the site and flares, tear gas, grenades, and other munitions. Many unexploded ordnances still remain on site. Now owned by Dow Chemical, the site is home to one of the country’s most contaminated hazardous waste landfills, full of toxins from decades of pesticide production.

“It’s the worst possible site for a commercial rocket facility,” says Lang. Every other vertical spaceport in the United States launches directly over the ocean. In the history of U.S. space flight, neither NASA nor the FAA has permitted a vertical launch over private homes or people immediately downrange.

But the proposed site adjacent to Cumberland Island would launch rockets over dozens of private residences and a national park that hosts 60,000 visitors each year. Part of the island is a federally designated Wilderness Area that protects endangered species and critical wildlife habitat.

Cumberland Island is also home to some of the oldest and most important African American cultural sites. Cumberland is part of the Gullah-Geechee heritage corridor. The Gullah-Geechee people protect and maintain structures from a historic slave settlement, a cemetery, and the First African Baptist Church—now directly in the flight path of the proposed rocket facility. Many of the Gullah-Geechee people still live close to the marshes that would be directly affected by rocket fuel and other hazardous wastes discharged by the facility.

Over 2,500 acres of state-owned marsh is being proposed for use as a debris containment area for the rocket launch site, which would violate Georgia’s Marshlands Protection Act. Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources can stop the project, and so can the FAA, but they would have to stand up to significant political pressure.

“DNR will do the right thing, follow the law, and protect our coastal resources if politicians let DNR do its job,” says Lang.

The Trump administration rolled out new regulations that gut the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and eliminate public comment on projects that require federal approval. As a result, the rocket facility’s new permit application will not include any public hearings or formal comment opportunities. A decision is expected in the spring of 2021.

Camden County commissioners say that the proposed rocket facility, dubbed Spaceport Camden, will bring more jobs and tourism. However, most residents of Camden County oppose the spaceport and the millions already spent. Many millions more could be squandered on a launch pad that never gets used, says Camden County resident Steve Weinkle. After five years, Camden County commissioners have failed to lure a single company to use the proposed site.

“Taxpayers will be paying for decades,” says Weinkle.

And even if Camden County receives a permit to construct the site, it is unlikely that the FAA would ever issue an actual launch license, adds Lang. The FAA requirements for launching rockets are much more stringent than the requirements for a site permit.

Even local fishermen oppose the project, since rocket launches would close their waters to fishing for long stretches. Greg Hildreth has been commercially fishing in the waters near Cumberland Island for decades. At a public meeting in 2018, he said that the rocket facility would “hurt my business. For some private entity to come in and try to take that away from me, my other fellow captains, and recreational anglers, is unacceptable.”

A groundswell of local residents and organizations across the region hopes to convince the FAA not to issue any permits for the rocket facility. Southern Environmental Law Center has already taken legal action, and the FAA has already received a record-setting 15,600 comments—nearly all of them opposing the proposed rocket facility.

“One rocket failure over Cumberland could destroy centuries-old maritime forests, the habitat of multiple threatened and endangered species, and National Historic Districts,” says Jessica Howell-Edwards, program director of the nonprofit Wild Cumberland and organizer of the No Rockets Over Wilderness coalition. “National parks like Cumberland Island were not created to become debris fields for private rocket companies. They are cherished public lands that belong to us all.”

Want to comment on the proposed rocket facility threatening Cumberland Island? Submit your thoughts to the FAA and sign a petition at norocketsoverwilderness.org

Where are the Carnegies and Rockefellers?

Two of the wealthiest families in America have private residences on the island. So do the Candlers, the Coca-Cola heirs who are hoping to develop 88 acres of Cumberland Island, including a portion of the beach. Normally vocal and outspoken on issues facing Cumberland Island, these wealthy island families have been noticeably silent on the proposed rocket facility.

One reason may be that Camden County is considering a change to the island’s zoning laws to allow development of private property within the national seashore boundaries. Some of the island families have acknowledged that they will not oppose the commercial launch facility so that Camden County will zone their property in favor of their development plans.

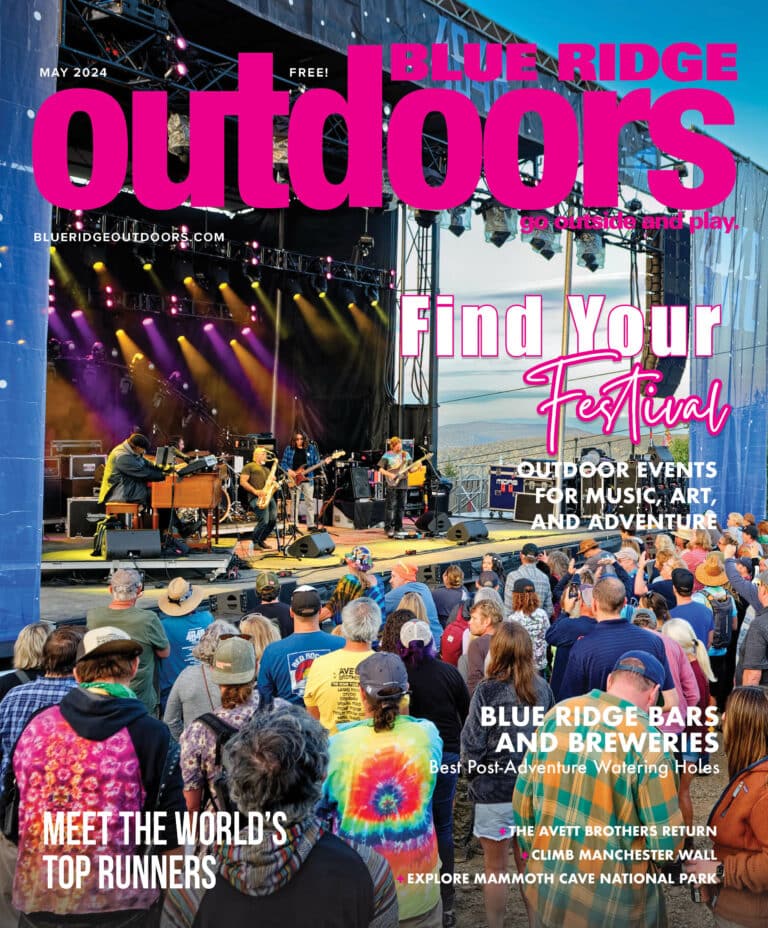

Cover photo: One of the most scenic destinations in the south, Cumberland Island National Seashore holds nearly 10,000 acres of federally designated wilderness. Photo courtesy of the author