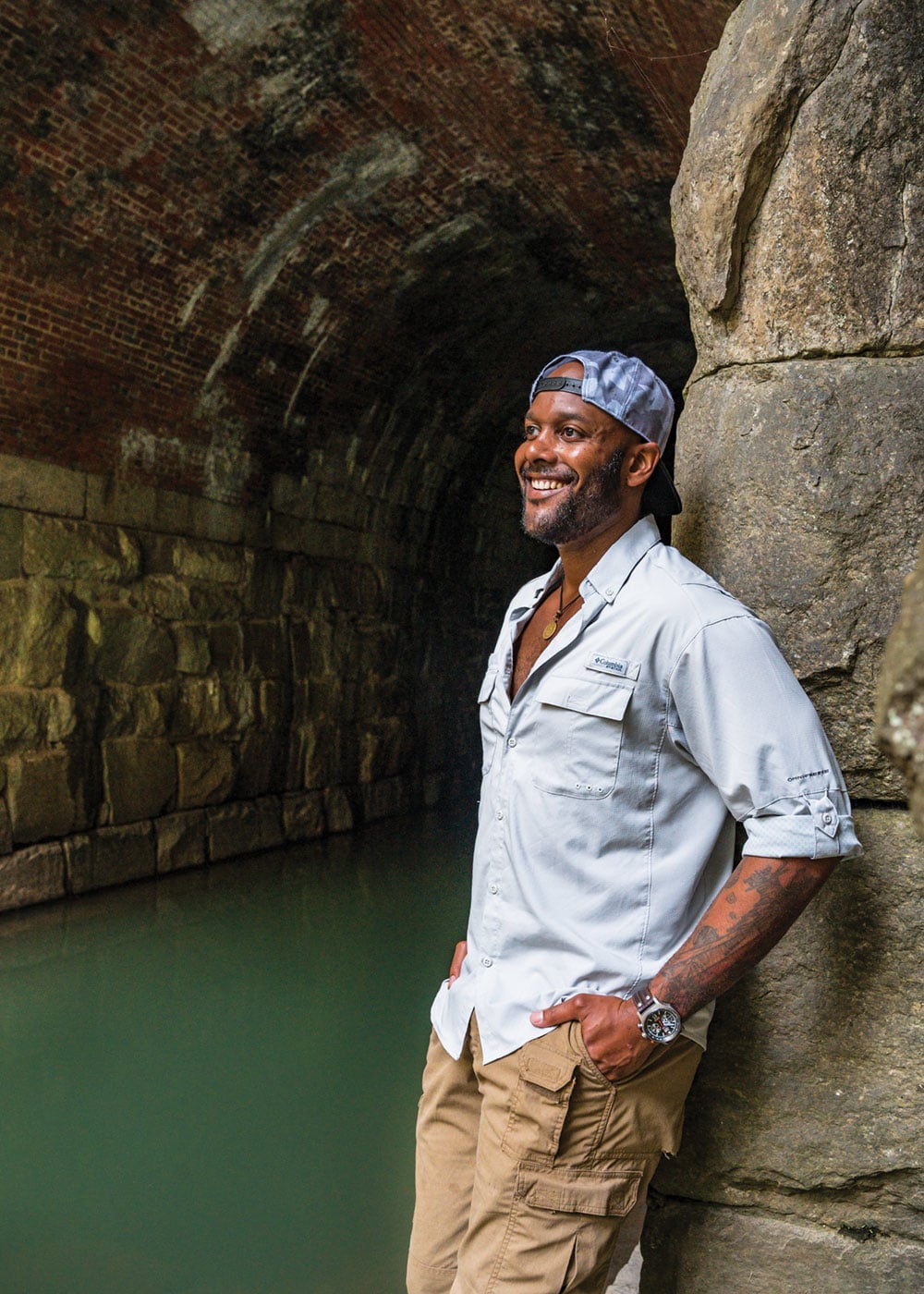

Relic Hunter Evan Woodard Recovers What’s Lost and Forgotten

From unmarked railroad spurs and children’s toys to more common items like oyster shells, glass bottles, and shoes, Evan Woodard never knows what he’s going to find when he goes relic hunting.

A devoted history enthusiast, Woodard routinely spends hours outside of his job in cybersecurity diving into old records, and when the pandemic hit in March, he found himself with a lot more time to get out and survey areas around Baltimore, Md. “Maps and research has always been something that I’ve loved,” he said. “So when I got into relic hunting, it came naturally. You need to really figure out what it is on your own.”

Using whatever resources he can find, from Sanborn maps and old atlases to records from the Library of Congress and archives from The Baltimore Sun, Woodard traces the location of old homesteads and warehouses to find abandoned dumps to sift through. “You are going into a place and trying to save history as fast as you can before it’s lost or destroyed,” Woodard said. A lot of these places have sat untouched and unused for decades, concealing evidence of what life was like 50, 100, or even 200 years ago.

Woodard is drawn to the entire process—studying maps for hours on end, lining up historical records with current locations, following clues to forgotten places, and piecing together stories to find out where an object came from. Since he started relic hunting, Woodard has formed a relationship with the Baltimore Museum of Industry, donating found items to fill in their collection. “It’s a really cool way to give back to what was my favorite museum as a kid, and is still my favorite museum as an adult,” he said.

Now when he’s out on a trail or even walking through town, Woodard is thinking about all of the forgotten history that might be found in that space. “There’s a lot that people just walk by every day,” he said. “When you think about what’s been lost or forgotten about, it can be something that people take for granted because they know it’s there but they don’t really know the history of it or what it’s doing there. It helps connect people to past generations.”

How do you use historical and modern maps to find old homesteads and dumps?

Very rarely are dumps marked on maps. If you know roughly where the house or the property is and have a topographical map next to it, you know that they’ll usually throw trash or debris into a ravine. So you look for low lying areas that are going to be away from the property but not too far. They’re mostly throwing it within 100 yards of the property.

Avenza loads historical USGS maps from the 1800s into your phone and lets you use them like a GPS map. So you can go out into the woods, link to that map, and it’ll show you roughly where you are within a few hundred meters. It gives you a really good estimation of where you should be walking and what direction you should be heading to. Those types of technologies, mixing old with new, are really cool. It helps you understand where to go and what to look for.

This morning, I was looking at one and was trying to find this B&O Railroad dump. I did find it but it took a while because all of the road names around it had changed so much since then, along with the water features. There was no known exact point of reference. It’s a lot of trial and error until you find some small clue and then boom, you’ve got it. You feel like you’re a part of the Scooby Doo Detective Agency. To finally find what you’re looking for is an amazing feeling.

If a site is on private property, Woodard makes sure to get permission from the owner before heading out. In most cases, he says people are really interested to see what he will find. If he wants to explore public property, he checks with park employees on regulations. Most parks do not allow digging below the surface in order to prevent damaging tree roots.

When you get to a site, what clues are you looking for to find the dump?

Look for trails. Even if it’s been 100 or 150 years since someone’s walked back there, there’s still going to be an actual trail from the humans that walked that path all the time to do the dumping. It was just such a common, daily occurrence so it’s worn into the ground.

Once you find an item, how do you go about trying to date it and learn its story?

Things that don’t have an embossing or any kind of labeling are really hard to track down or understand what it is. If it has an embossed label or stenciling, a business name, then I spend time tracing back into history and doing the research. That’s my biggest draw to this. I love history. I love research. I love figuring out and making a personal connection to each item. It’s not so much just who the manufacturer was or where they were based. For example, one of the items I found was a medicine bottle. I actually did a deep dive into [the pharmacist’s] story and found out that he sold heroin here in the city to younger kids and got put in jail. It was a huge crime at the turn of the century in the 1900s. That was a crazy thing to find out about versus just saying who the pharmacist was.

Google is not so much of a help anymore because of Etsy and eBay. The first 20 pages when you type in an item to Google about a glass bottle with XYZ stamped on it, you’re going to get a lot of hits like that. So that doesn’t really help you research it or date it. When it comes to dating, you have to look at the seams on the bottle, if there are air bubbles in the bottle, how heavy it is, what kind of top it is. There are little indications of what type of molding was used to make the bottle.

In what ways have you seen nature reclaim space after a site has been abandoned?

It’s pretty crazy to see how fast something like a river or stream can change in a hundred years. Recently I was at a site and what should have been a nice S curve was completely gone. It’s just wild to see how Mother Nature is out there doing her own thing.

Some of the glass items that I’ve come across, especially the enclosed ones that are complete, easily turn into their own terrariums without me having to go to a florist. They’re beautiful pieces of art that I could put on my shelf if I wanted to. It‘s so wonderful to see that even though this glass takes millions of years to break down, nature is still working its way around it.

Why did you decide to start documenting your process on Instagram (@salvagearc)?

I didn’t expect anything of it. I just thought I could find some other history nerds to chat and connect with. Social media has really allowed me the opportunity to take something that I really love, like history, and to share it with others.

I’d love for people to get more involved with this. There’s stuff everywhere. The research is a lot, but if you put the time in, it’s going to be super rewarding. You pull your first bottle—that’s all it takes is that one item.

Do you have a favorite relic that you’ve found?

I’m really into collecting flasks and liquor/alcohol bottles because of the designs they have on them. They all have a personal story. There is a glass I have from Baltimore Glassworks. The factory burned down, but when it reopened, they made this commemorative glass in the 1850s that had a phoenix rising from the ashes. It just looks beautiful, the coloring in it and a very intricate design.

Cover photo: Relic hunting is a way for Evan Woodard to combine his love for history and research with getting outside. Photo by Zach (@Zachsadventures)