Viewed Online for the First Time, the South’s Iconic Class V Paddling Race Expands Its Reach

“You see that?” asks Green River Narrows Race event organizer John Grace, during a Zoom interview a week after hosting what’s known as the “largest extreme kayak race in the world.”

Squinting at my computer screen, I can just make out a dot a few pixels wide perched on the tip of a finger.

“That’s a tick head,” Grace says.

In a normal year, sweeping up after the annual fall Southern paddling race means Grace grabs a forgotten koozie or picks up the occasional piece of trash. But back in November—during the anything-but-normal-year that was 2020—he found himself bushwhacking through the Green River Gorge, schlepping a 3,000-foot roll of fiber optic cable and hundreds of pounds of video equipment, as well as a few ticks.

For the last 25 years, whitewater paddlers have come from around the world to western North Carolina to race the steepest mile of the Green Narrows. The rugged rapids always give boaters big challenges, but 2020 brought a whole new set of obstacles to navigate.

After putting on a successful mountain bike race in the Green River Game Lands in July, Grace was cautiously optimistic that the whitewater event could happen in November. The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission is the primary custodian of the game lands, and according to Grace, “They stressed the importance of adhering to state mandates and social distancing but overall were supportive of the race happening.”

Coronavirus restrictions hadn’t been too difficult to manage for a small local bike race, but the Green Race has grown considerably from its humble roots. With nice autumn weather on race day, it’s not uncommon to see several thousand spectators lining the banks along the river’s most iconic rapids. This popularity is part of what makes the event so special, but it was also going to pose a major public health problem. “As fall got closer, we started looking at our options, and spectators were obviously the biggest problem,” Grace acknowledged. “On a normal year, people are in there right on top of each other for at least three hours. It was a tough call, but with less than two months before the race, we decided to do it without spectators.”

Grace has pondered the idea of a Green Race livestream for almost a decade, but previously the cost and logistical challenges have deterred him. In 2020, giving people the opportunity to experience the event from their homes felt more important than ever. To help cover some of the overhead, he decided the race would be offered via a pay-per-view format. “Once we made the decision, we started scrambling to get everything dialed.”

After a successful backyard equipment check, the event crew hauled computers, cameras, tripods, and cables into the gorge, plus a generator to power it all. A second check happened the weekend before the competition, with a small group of paddlers sprinting the course at 200% flows in a practice event dubbed “The Running of the Bulls.”

The race theme was “The Show Must Go On,” and athletes wore numbered bibs designed to look like medical scrubs. In true 2020 style, the livestream website crashed 10 minutes before reigning champ Dane Jackson was scheduled to leave the starting line. “One of the plugins that we updated on the website to the most recent version had locked up and caused the site to go down,” says Grace. “We reinstalled the older version and it was back up in 15 minutes.”

Clearly nobody told Jackson about the technical difficulties—the Tennessee native would go on to win his fourth race, setting a course record of 4:02.3.

Despite the hiccups, streaming the race allowed people from around the world to participate in an event that’s become a staple of the competitive whitewater paddling scene. The coverage also piqued the interest of a few media companies curious about adding the race to their sports rotation, but Grace isn’t so sure the event needs television producers in charge. “Every year, more and more people are interested in the Green Race, and that’s great,” he says. “But I’m fine with a more organic, gradual growth versus some exponential increase in exposure that totally transforms the character of the event. I’ve been racing the Green for a long time, and paddling up to the starting line still hits you the same way every year. I would never want to sacrifice that for a show.”

While Grace isn’t ready for the Green Race itself to transform, the event has left an indelible mark on whitewater paddling. In the early 2000s, brands were pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars into freestyle kayaking and canoeing, and rodeos were taking place around the world. Grace approached a billion-dollar brand and asked for a $500 sponsorship for Green Race T-shirts and other expenses. “Long story short, they said no because they thought a race down these rapids wasn’t a good idea,” Grace says.

He did it anyway, and it caught on. As competitors got better and faster, companies like Dagger and Liquidlogic began to design prototype boats that would help their athletes bring home a win on the Green—designs that would eventually go into production for the masses and fuel increased enthusiasm for speed on the water. “Now, you’ve got Class V races around the country like the North Fork [Payette], and races on more intermediate runs like the Ocoee are getting triple-digit participants.”

The race has also influenced paddling styles and how boaters train. “The Green Race has given normal, class V kayakers a season where they actually train and get super fit, but it also makes you better year-round,” Grace adds. “You have to learn to carry speed, minimize corrections, and shut everything out but the river.”

Perennial competitors look forward to finding flow as they navigate the turbulence of the Green River, and Grace is confident that the Green Race will continue to provide that opportunity year after year. “The Green Race is like death and taxes,” he says. “It’s there, and it’s going to happen.”

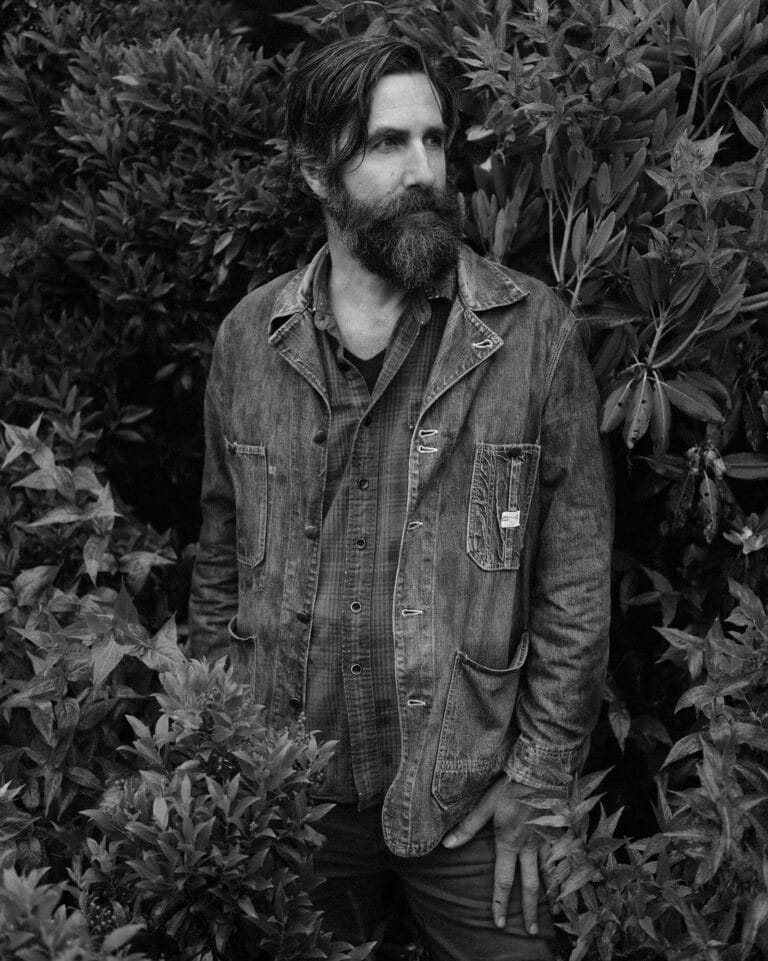

Cover photo: A production crew hauled computers into the remote Green River gorge to livestream the annual race. photo by Marc Hunt