Exploring the South’s Next Wilderness

The farthest you can get from a road in the continental U.S. is 22 miles, in a deep corner of Yellowstone National Park. In the Southeast, the farthest is around five miles—in places like Tennessee’s Upper River Bald Wilderness Study Area. It’s an area so rugged, remote, and rarely traveled that locals call it the “Heart of Darkness.” Today I am hiking it with Jeffrey Hunter, the Tennessee field coordinator for the Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition, who has been working tirelessly over the past two years to protect the Upper Bald River Wilderness Study Area permanently as Wilderness.

It’s been 25 years since any new Wilderness has been designated in Tennessee. Last year, President Obama signed the Omnibus Land Management Act that created more than 1.6 million acres of Wilderness across the United States, including 37,000 acres in West Virginia and 43,000 acres in Virginia. But Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, and South Carolina, were left out of the bill.

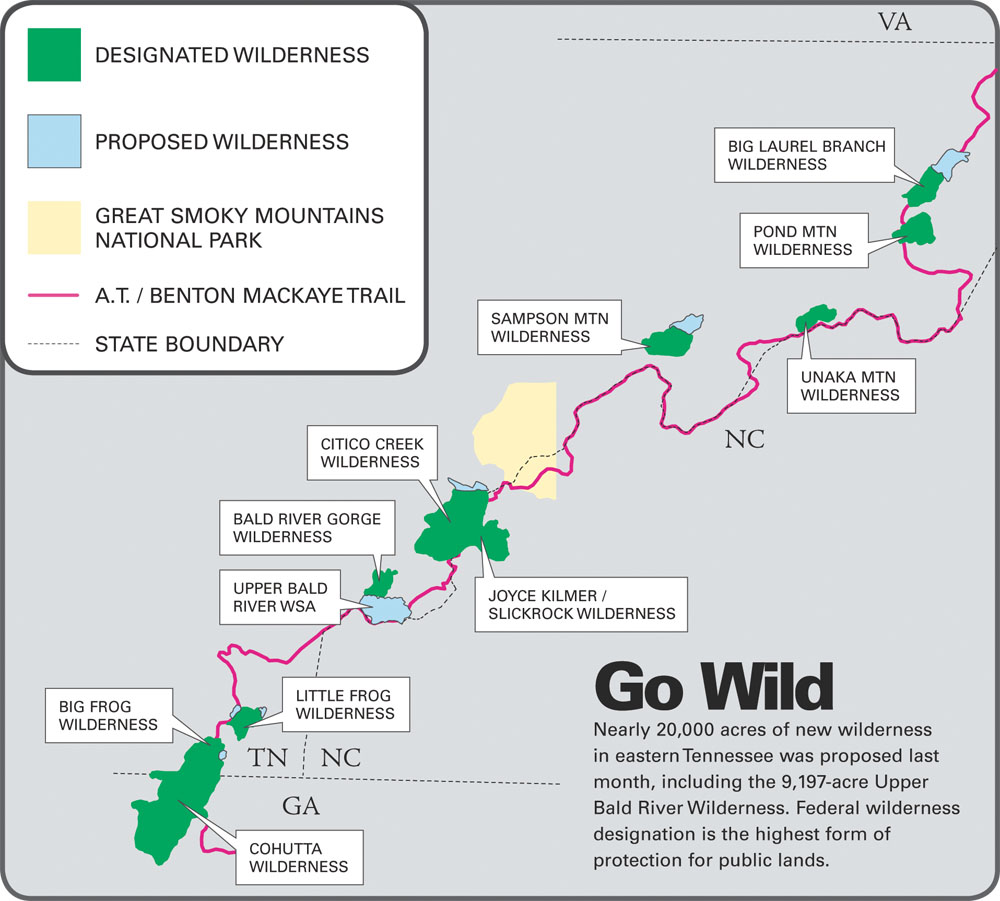

However, last month Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) introduced the Tennessee Wilderness Act, which if passed, would create almost 20,000 acres of new Wilderness in Eastern Tennessee, including the 9,197-acre Upper Bald. It’s one of the most remote tracts of land in the Cherokee, rising from the Bald River valley floor to the 4,000-foot-high ridges that define the Tennessee-North Carolina border. Most hikers flock to portions of the Cherokee and Nantahala National Forest that are easier to access, leaving the Upper Bald, which is a good half hour’s drive beyond the popular Bald River Falls trailhead, to only the most dedicated outdoor enthusiasts who seek something that has become increasingly elusive in the Southern Appalachians: solitude.

We start our hike crossing the Bald River on a downed white pine, then follow an old railroad grade upstream. Like most of the Southern Appalachians, the Upper Bald was logged heavily in the early 1900s, but has rebounded since. Today, the forest is a hotbed of biodiversity.

The Upper Bald was recommended for Wilderness by the Forest Service in 2004 and has been managed passively as Wilderness since then. But it takes an act of Congress to designate an area as Wilderness. According to the Wilderness Act, no roads, structures, motorized vehicles, or even bicycles are allowed. Wilderness is intended to be a place where Mother Nature still calls the shots.

The Wilderness Act is almost philosophical in its nature, and there has been much debate since its passage of the spiritual value of Wilderness to our society. Convincing the American public and our politicians that solitude is a resource that needs to be valued and protected just like clean water and fresh air can be an uphill battle.

“There are two ways you can get a Wilderness bill introduced,” says Carol Lena Miller, a member of the Virginia Wilderness Committee. “You either need a local congressional representative who is a Wilderness champion, or you need overwhelming grassroots support from that representative’s constituency. It is completely political.”

Most of the big Wilderness areas are out West; in the Southeast, less than 0.5 percent—roughly 1.1 million acres—is protected as Wilderness. Hunter hopes to boost that number by 9,197 acres with the addition of the Upper Bald.

We hike alongside the Bald River for a couple of miles, passing a 12-foot waterfall along the way. The Upper Bald has several crashing cascades, but none as dramatic as the uber-popular Bald River Falls several miles downstream, which attracts thousands of visitors every year and is one of the most photographed waterfalls. The falls is already protected as part of the Bald River Gorge Wilderness, but the headwaters for the Bald remain unprotected.

“More than anything, we’re seeking this designation because of water,” says Hunter. The Upper Bald headwaters and feeder creeks flow into the Bald River, which flows into the Tellico River and then the Tennessee River, which supplies water for millions of people in East Tennessee.

The trees get thicker and taller the higher we climb. The loggers from a hundred years ago left the stands of trees on the steepest slopes, so small pockets of old growth can be found in this forest. Hunter points out specific trees as we climb and only takes breaks to listen to the calls of songbirds, whispering the bird’s identity after the call subsides. Hunter gets excited about tiny plants that most of us would overlook on a hike through the woods. He seems to be in tune with the subtle beauties of this particular forest. This is the sort of attention to detail that you almost have to have to appreciate the Upper Bald River Wilderness Study Area.

Unlike its neighbor, the Bald River Gorge Wilderness, the Upper Bald’s value doesn’t hit you right in the face. There are no panoramic vistas or towering waterfalls that are popular with the masses. Its beauty is in its pristine headwaters and lush biodiversity, which are a harder sell to the general public.

I don’t fully appreciate the value of the Upper Bald myself until several hours into our hike. We haven’t crossed paths with anyone except boars, bobcats, and birds. And the only sounds I’ve heard—aside from our own hushed voices—are water and wind. I’m elated knowing that I am as far as I can reasonably get from the nearest car or television, that I am immersed in a forest that is as pristine as one can get in my part of the world. •

HIKE IT YOURSELF

The Upper Bald Wilderness Study Area has a diverse suite of trails that take you from the river floor to the ridgeline. It’s several miles by foot to the most remote stretch of the State Line Trail (aka Benton Mackaye Trail), but there are good campsites along the ridge and two springs with reliable water. Shorter, out and back day hikes are possible as well.

directions

The Upper Bald River Wilderness Study Area is located 20 miles east of Tellico Plains, Tennessee, off the western end of the Cherohala Skyway. From the Skyway, take the Tellico River Road south for 6.5 miles, then turn right on Bald River Road, driving another six miles to the Campsite 11 trailhead for Brookshire Creek.

brookshire creek trail

A six-mile trail beginning at Bald River Road that follows the Bald River, then makes its way up the Brookshire Creek as it drops off the ridgeline. There is great camping along the Bald River, and a half-mile side-hike to Beaverdam Bald at the end of the trail. Beaverdam has expansive views of the Wilderness study area.

kirkland creek trail

Kirkland Creek Trail: This 4.3-mile trail crisscrosses a crystal clear mountain stream before climbing to Sandy Gap where it meets Stateline/Benton Mackaye. You’ll cross the creek 11 times (22 if you do this as an out and back) so wear water shoes. There’s great creek-side camping only a few miles from the trailhead on Bald River Road.

stateline trail / benton mackaye trail

5.7 miles of the Stateline Trail runs on the border of the proposed Wilderness area from Sandy Gap to Sledrunner Gap. This is the section of the BMT known as the “Heart of Darkness” because it’s so remote and difficult to maintain. The trail is faint in several areas from lack of use, but stay on top of the ridge and you’ll be able to find your way. You’ll have partial views throughout the entire hike and pass a border survey marker from the 1800s.

A WILDER TENNESSEE

The Upper Bald is the only stand-alone tract being proposed as Wilderness in Alexander’s bill, but there are some other Wilderness expansions for hikers to explore if the bill is passed:

Joyce Kilmer/Slickrock Wilderness Addition

The bill would add 1,973 acres to Kilmer/Slickrock, providing a permanent corridor for black bear and other wildlife passing between the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the 33,000 acres of Wilderness that already exists in the Kilmer-Slickrock and Citico Creek Wilderness areas.

Big Frog Wilderness Addition

Combined with Georgia’s Cohutta Wilderness, the Big Frog is part of the largest Wilderness area in the Southern Appalachians. The Cohutta-Big Frog complex (separated only by the state line) is 45,059 acres. This bill would add 4,400 acres to the northern boundary of the Big Frog Wilderness, which encompasses the headwaters of the Conasauga River.

Big Laurel Branch Addition

This 5,589 addition to the popular Big Laurel Branch Wilderness would protect 4.5 miles of the Appalachian Trail running from the Iron Mountain Shelter to Vandeveter Shelter.

Sampson Mountain Wilderness Addition

The bill would add 3,069 acres to the northern edge of the existing Sampson Mountain Wilderness, bringing Flattop Mountain into permanent protection.

ROADLESS FOR TOMORROW

How much roadless area is left in the Southern Appalachians? Not much, according to Wilderness advocates.

“In the East, there are so few places with no roads left. And our forests are unique because they’re so close to high population zones. The Chattahoochee is an hour from six million people, so we have an unusually high visitation rate,” says Wayne Jenkins, executive director of the Georgia Forest Watch, adding that ensuring the few existing roadless areas left in our forests is paramount to overall forest health. Here’s how each state in our region stacks up for roadless areas still open for potential wilderness protection:

Georgia: 61,557 acres in the Chattahoochee National Forest

South Carolina: 6,161 acres in the Sumter National Forest

North Carolina: 52,786 in the Nantahala National Forest, 99,592 in Pisgah National Forest

Tennessee: 86,805 in the Cherokee National Forest

Virginia: 163,894 acres in Jefferson National Forest, 251,985 in the George Washington National Forest

West Virginia: 202,000 acres in the Monongahela National Forest

Maryland: 0 (no national forest land)

THE NEXT, NEXT WILDERNESS?

The public lands bill that President Obama signed in 2009 created new Wilderness in Virginia and West Virginia, but several Southern states were left out of that lands package. Alexander’s Wilderness bill hopes to end Tennessee’s 25-year Wilderness drought, and advocates in other states are still working to add acres to the Southern Appalachian’s Wilderness portfolio. Here are some of the most significant lands Wilderness advocates are hoping to protect in the coming years.

VIRGINIA

President Obama signed into law 43,000 acres of new Wilderness in Virginia in 2009, all of which lies inside the Jefferson National Forest. But the George Washington National Forest actually has the highest concentration of roadless areas in the Southeast. Advocates are pushing for a massive Shenandoah National Scenic Area that would protect 115,000 acres of the Shenandoah Mountain, including five roadless areas with Wilderness potential. It will likely be years before a bill is introduced that would permanently protect the land on Shenandoah Mountain, but here are two roadless areas that should top the list for Wilderness.

Skidmore Fork Roadless Area

Skidmore Fork is a 5,228-acre that includes a 1,400 acre patch of old growth in the headwaters of Skidmore Fork. It would protect the drainage that flows into the Switzer Reservoir, which is the main water source for Harrisonburg. It’s bordered by the Shenandoah Mountain Trail and the decommissioned Railroad Hollow Trail.

Little River Roadless Area

The 12,490 acres that advocates are proposing for Wilderness is in the heart of a larger, 28,000-acre roadless area. The proposed Wilderness includes the entire watershed of the Little River, as well as an extensive trail network. The Friends of Shenandoah Mountain have worked with mountain bikers, recommending Wilderness for only the core 12,000 acres, allowing mountain bikers to continue using the trail system surrounding it. Buck Mountain Trail (7.5 miles) and Big Ridge/Grooms Ridge Trail (4 miles) are inside the proposed Wilderness.

GEORGIA

The largest roadless area remaining is 13,000-acre Mountaintown Creek, which includes seven miles of the Benton Mackaye Trail and the steep Mountaintown Creek Trail, which is popular with bikers, hikers, and anglers. Because of its popularity as both a hiking and mountain biking destination, Georgia Forest Watch and Friends of Mountaintown proposed designating Mountaintown as a National Scenic Area, but the proposal languished. “We could continue to pursue a National Scenic Area designation or we could go for full blown Wilderness,” says Wayne Jenkins, executive director of Georgia ForestWatch. “Right now, we’re working on building grassroots support for protection for Mountaintown.”

NORTH CAROLINA

The Sierra Club has been trying to put Wilderness on the radar of the two Congressional representatives from Western North Carolina (Heath Shuler, Virginia Fox), but so far, the representatives have been unreceptive. That doesn’t mean there isn’t Wilderness potential in the Pisgah and Nantahala National Forests. There are five areas in Western N.C. that the Forest Service has designated as Wilderness Study Areas:

Lost Cove Wilderness Study Area

This 5,710-acre forest in N.C.’s High Country is visible from the Parkway and contains the Big Lost Cove Cliffs, Hunt Fish Falls, Gragg Prong Falls, as well as a piece of the Mountains To Sea Trail.

Harper Creek Wilderness Study Area

Adjacent to Lost Cove, this 7,140-acre tract has a handful of destination-worthy waterfalls, pockets of old growth, tons of rock and cliffs, and an extensive trail system.

Craggy Mountain Wilderness Study Area

Large pockets of 350-year-old trees can be found in this 2,380-acre forest near the popular Craggy Mountain Scenic Area, just off of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Overflow Wilderness Study Area

Overflow is 3,200 acres of steep slopes and waterfalls in the headwaters basin of the Chattooga National Wild and Scenic Area. A piece of the Bartram Trail crosses through the upper portion of the tract.

Snowbird Wilderness Study Area

Rugged 5,400-foot mountains and massive waterfalls make this 8,490 acres popular with hikers. Almost nine miles of Snowbird Creek, which qualifies for National Wild and Scenic designation, are located within the study area.