Erwan Le Corre, a French-born free diver, ultra runner, rock climber, grappler, and all-around athlete is the creator of MovNat, a training system designed to reintroduce modern man to the natural movements and escape the overweight, overspecialized beings we are today. MovNat takes the athletes out of the gym or specific sports like cycling and puts them into the wilderness where he’ll sprint up hills, climb trees, crawl through brush, carry boulders, balance on logs—all the skills our distant ancestors had to have in order to survive back when survival depended more on physical fitness than on 401(k) returns.

“We all have these instinctual movement patterns built into our primal memories,” Le Corre says. The problem is that in today’s world, we’ve moved beyond these instinctual patterns into specialized movements and skills. As a result, we have body builders who can bench press 400 pounds, but can’t run a mile. Marathon runners who couldn’t lift their own body weight. Gym rats who have forgotten how to jump or sprint. Office rats who have forgotten how to climb a tree.

“I see a world coming where ‘walking’ will become just a notion,” Le Corre says. “A skill of the past. A world where people will have to learn how to walk again.”

Le Corre has a name for the condition he’s lamenting. He calls it the “Zoo Human Syndrome,” a physical, mental, and spiritual funk brought on by overspecialization and a general disconnection from our natural selves.

“Specialization in sport and in life is a domestication process. It’s resulted in the human zoo, with specialized workers in a square room who trade their square office for square gyms and treadmills,” Le Corre says. “We all suffer from this zoo human syndrome. It disconnects us from our true nature, from the beautiful human animals we are. We now live in an environment that is unnatural: the office, the gym, the home, the pollution, the car. When you accumulate all of these things, it makes for toxic parameters, and the human animal can not thrive.”

In short, man has been fully domesticated, and we’re miserable because of it. There’s a good bit of science to back up Le Corre’s philosophy. One in five Americans will suffer from severe depression at some point in their life, and more psychologists are recognizing the role of “nature deficit” in clinical depression. Separate studies performed at the University of Illinois and England’s Essex University suggest that outdoor exercise is a more effective treatment for depression than pharmaceuticals. Forget depression, take a look at the obesity rates and rising instances of heart disease and type 2 diabetes, and you might come to the conclusion that our society has strayed too far from our natural, physical selves. Even fit athletes who dominate their sport suffer from side effects of the Zoo Human syndrome.

Overspecialization in one discipline can lead to repetitive stress injuries, like the shin splints and bad knees of runners or the lower back pain of cyclists. If you’re a competitive swimmer, there’s a good chance you’ve already had at least one shoulder surgery.

“If you repeat the same motion over and over, eventually, your body rejects that motion,” Le Corre says. Instead of mastering one sport, humans are meant to be competent in all athletic activities. “From an evolutionary perspective, humans have been successful because we were able to master a whole range of movement skills. We don’t just swim; we climb, we run, we crawl, we jump.”

The variety of movement skills allowed us to adapt to a range of habitats, and hunt a spectrum of prey. Le Corre wants us to return to the basic knowledge of movement that allowed humans to be so successful. Even though you’re in no danger of having to chase down a wild animal for dinner, there are still practical applications for becoming a movement “generalist.” Being able to run 100 miles straight or bench press 400 pounds is neat, but these aren’t necessarily functional skills in nature or the city. Being strong enough to carry your wife out of the woods when she breaks her leg, or adept enough to swim across the current when you fall into a river, or able to jump out of a second story window and land without breaking your neck–that’s functional fitness. And that’s where Le Corre would like to take his students. To the point that they’re so well-rounded and physically fit, that they can handle themselves in any given situation. The goal is to create “generalist” athletes who can do the basic movement skills that made us so successful in the first place: sprint, jump, swim, crawl, climb, and fight.

It’s a philosophy based on an obscure French form of training created by Georges Hebert in 1902 called Methode Naturelle. After seeing disaster strike an island and an entire population too unfit to save themselves, Hebert developed a training method based on the principle that it is possible to arrive at a high degree of physical development without the help of devices or facilities, simply by imitating the natural gestures of men living in nature. Hebert wanted to ensure his French countrymen were physically fit enough to take care of themselves and each other in any situation. His motto was “to be strong to be useful.” Le Corre’s MovNat is a re-imagining of Herbert’s Methode Naturelle, stripped of Hebert’s moral undertones and repackaged for the 21st century.

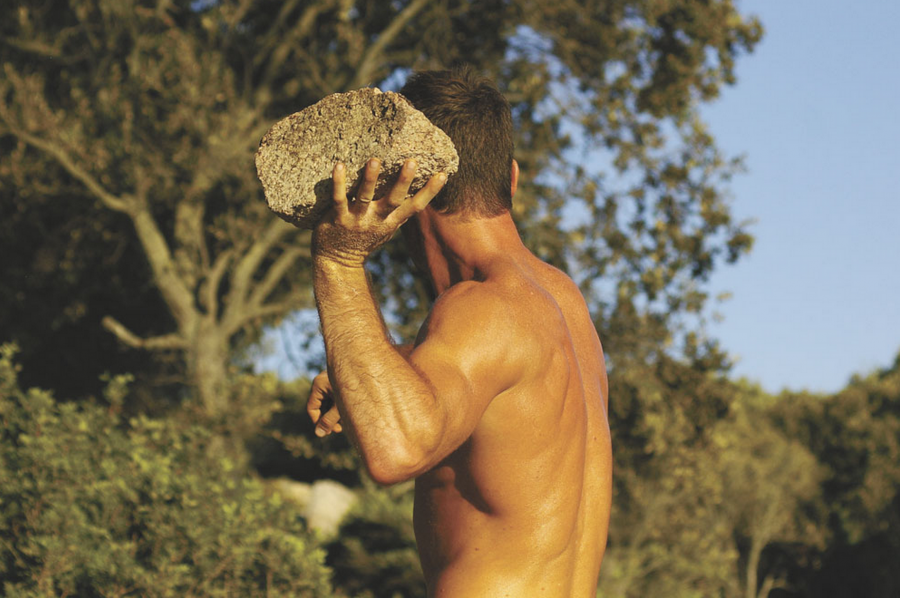

I watched a Youtube video of Le Corre practicing MovNat in Brazil. In the short clip, he’s shirtless and barefoot running through the woods, then sprinting on the beach, pulling himself up and over boulders, cliff jumping into the surf, swimming through crystal clear rivers. It’s a beautiful clip that makes MovNat look slick and effortless, but how practical is it? Can MovNat’s principles be applied to the Southern Appalachians or the neighborhood park? And more importantly, can you really get fit by mimicking the movements that our luxurious lifestyles have rendered nearly obsolete.

Le Corre is confident in his method: “MovNat is very simple and very accessible. Forget about the crazy stunts you see in TV or the movies. The first rule of survival is to avoid trauma. You never want to be hurt. So you progress gradually. You explore first. That’s the most important element. Exploration. But train in this way and you will progress. You will become strong. Not strong as in big guns, but strong as in fit. You will be prepared for whatever may come.”

The first time I tried to incorporate MovNat methods, I was running my standard four-mile loop through my neighborhood trails. I saw a low boulder, maybe three feet high, and inspired by Le Corre’s video, I decided to jump on top of it and bound off, maintaining my stride. Then I saw a park bench. So I vaulted over that. Then I saw a downed log, so I walked across it as if it were a high wire. I ended up climbing trees for 30 minutes. It was less of a run and more of an exploration of my surroundings—just like when I was a kid, romping through the woods in my neighborhood. The movements felt foreign, and I was completely self-conscious, worried that someone would see me out there in the woods, acting like a kid.

“Most people who see me training don’t understand what I’m doing,” Le Corre says. “They see people carrying a rock or leaping on a boulder, and they don’t understand the movements. It’s crazy to realize people don’t recognize natural movements any more.”

“Most people who see me training don’t understand what I’m doing,” Le Corre says. “They see people carrying a rock or leaping on a boulder, and they don’t understand the movements. It’s crazy to realize people don’t recognize natural movements any more.”

I’m the perfect example of this phenomenon. Being fully enveloped by my Zoo Human existence, I actually had to re-learn how to climb a tree. Eventually, my movements transitioned from awkward and self-conscious to fluid and carefree. I was having fun, but was it a solid workout? Without knocking off a certain number of bicep curl reps and sit-ups, how could I gauge how hard I had worked? My question was answered the next day, when I woke to find scrapes on my legs, blisters on my hands, and muscle soreness in places I didn’t know I had muscles. If I was this sore and fatigued from a 45-minute run with some tree climbing and boulder hopping thrown in, what sort of condition would I be in after a full-blown MovNat workout?

If you want to get a true sense for the kind of workout that Le Corre is pushing, watch a child play in the backyard. He jumps from a boulder, sprints to a log, falls down and starts crawling. Then he stands up, balances on a log, picks up a rock and throws it. Then he climbs a tree. And then does it all again, and again.

“Kids are our guides. They show us the way,” Le Corre says. “They have no predefined notion of fitness. It’s all play and exploration.”

And while they play, their imagination is working. The child’s imagination gives each movement more intensity. Here’s an example. Try to walk across a log, balancing and not falling. Now, try to walk across that same log as if there is a raging current of whitewater below it and to fall means certain death.

The key to MovNat, is connecting these movements into a seamless pattern. Armed with the basic principles of Le Corre’s method and some suggested exercises, I head to my neighborhood park. I scribbled the workout on a sheet of paper and kept it with me, my Zoo Human brain still grasping for some sort of routine, some sort of quantifiable progression. I don’t want to do it wrong. I don’t want to miss a muscle group. The park has a baseball field, basketball court, playground. There are hills, trees, benches, rocks, fences—everything Le Corre says I’ll need.

I began the movements Le Corre set out for me slowly, starting with a jog that leads into a series of long jumps. Then monkey crawls into full sprints. Then broad jumps and crab crawls. At first, I consulted my cheat sheet constantly, making sure I hit the right number of reps, follow the specific progression of movements. I moved from crawling to sprinting to climbing to jumping to shadow boxing, just as it’s laid out for me by Le Corre. I’d played baseball and basketball in this park before, but never anything like this. Again, I moved from awkward, self-conscious movements to joyful, carefree play. And then something extraordinary happened. My imagination kicked in, and I started getting excited about random objects I found in the park, like a parking gate and a 20-foot high fence. With MovNat on my brain, the parking gate didn’t just keep my car out of the parking lot, it served as a barrier to vault over and crawl under. The fence didn’t just keep stray softballs from hitting spectators, it gave me the opportunity to test my climbing prowess.

The more I played at MovNat, the more potential for movement and training I saw in the environment around me.

“Usually, runners run for distance or time. They see the trail, and that’s it,” Le Corre says. “But think about how a kayaker reads the water. He sees things, ways to play in the water that people who aren’t kayakers can’t see. A climber sees a rock wall completely different than a non-climber. He reads the rock in a way that you don’t. To non-climbers, a rock cliff is a rock cliff, but to climbers, the rock cliff is a source of play. The more you explore your natural movements, the more you’ll see. The more you’ll feel like an animal.”

And this is where the true benefit of MovNat is found. Yes, this will get you into shape. Do it long enough and it will turn you into a generalist—a holistically fit individual. But it also opens your eyes to the potential of the world around you. Before MovNat, a park bench was for sitting. After MovNat, a park bench is a balance beam. A box jump. A vault. It is a complete conditioning device. I am moving in a way I’ve never moved before and I’m perceiving the world in a completely different manner.

Of all the elements that contribute to the domestication found within Le Corre’s Zoo Human Syndrome, our training methods are the most simple to adjust. But changing the way we train may just be the catalyst for more significant changes in our life.

“We’re not supposed to be depressed. We’re supposed to be happy. We’re not supposed to be obese, we’re supposed to be fit. When we stop moving, that’s when we get into trouble,” Le Corre says. “If people change the way they move, they change their experience. They change their perception. They change the way they think.” •

According to Le Corre, there are 12 key natural movements incorporated into MovNat.

“These natural movements belong to everyone. We all have these instinctual movement patterns built into our primal memories,” Le Corre says. “Most people need coaching through these movements because they’ve been disconnected for too long from their true nature.”

The 12 key movements of MovNat:

Walking

Running

Jumping

Balancing

Walking on all fours

Climbing

Lifting

Carrying

Throwing

Catching

Defending

Swimming

Here are five exercises that incorporate some of these movements to get you started.

Tree climbing: Find a tree and climb it. For an extra workout, climb up and through one tree, drop to the ground, sprint to another tree, climb up and through and continue until exhaustion.

Monkey Walk: Crawl on all fours with your chest facing the ground. Get your legs wide and try to keep your butt low.

Crab walk: The reverse of the monkey walk, you’re on all fours but with your chest facing upwards. Works the shoulders, core, and legs.

Balance beam squat: Stand on a log. Once you’re comfortable with walking across the entire log, incorporate full squats. Each step you take forward, drop so your butt is almost touching the log. Maintain balance and rise. Take another step and repeat until you reach the other side.

Run and throw: With a partner, pick up a moderately heavy rock. With rock gripped in both hands, start running at a casual pace parallel to your partner. Toss the rock to your partner while on the run. When he tosses it back to you, catch it on the run and continue.

Four More Questions for Erwan LeCorre:

You describe 12 natural movements within MovNat, what’s the most important?

Running is the most essential skill. In most situations, running is your best option. They say, “run for your life,” not swim or climb for your life. But you can’t disregard certain movements. Imagine yourself in a situation where you have to balance across a log to reach safety. All of a sudden, that skill becomes very important. So it’s hard to define a hierarchy of skills. To be most effective, you need to be able to do all things.

Does MovNat address more than just a person’s physical health?

The Zoo Human is like taking a wild animal and putting him in a zoo. Yes, he will live longer, but will he live happy? MovNat goes beyond exercise. Natural movement is one of several lifestyle matters that need to be changed. It aims to rehab the way we move, but hopefully, people will also look at the air we breathe, the food we eat, the way we sleep. There are plenty of coping mechanisms available to help you cope with your physical, mental, and spiritual suffering. TV, alcohol, money, drugs. But they only treat the symptoms, not the cause. You have to respect the needs of your true nature, and be aware of the zoo life. Without this perception, you can’t change anything. People don’t need another fitness method. People are hungry for meaning. For nature. MovNat is a complete education system that empowers zoo humans to experience their true nature.

MovNat is designed to develop athletic “generalists,” but what’s wrong with being a specialist?

There’s nothing inherently wrong about specializing. When you specialize, you make greater progress in a given field, and have the bliss of mastering something. Now it also often causes chronic injuries, can cause physical imbalances in the body, or can just get boring. Also for preparedness for real-world situations, specializing would lead to failure. If you are a runner but are pushed to a wall and cannot run, you have to fight back. If you are a fighter but have to escape a flood, maybe you need to climb.

Why is it so important to re-learn these primitive movement skills? Why do I need to know how to climb a tree and fight?

The modern lifestyle has made natural movement skills optional. So why run? Why jump? Why…walk? Because even a highly civilized world holds a multitude of situations where our evolutionary capacities remain indispensable. MovNat training emphasizes the body’s natural ability to move in an adaptive manner, in relation to a situation or context. Consequently, the movements trained can always be linked to a practical application that justifies them. MovNat trains you to become a well-rounded natural athlete, ready for a wide range of practical actions in various kinds of situations.