Gastonia, North Carolina, is a place that often feels like a no-place; I can say that because I grew up there. Perhaps this is because Gaston County is stuck between two separate but definable regions of North Carolina: the mountains and the piedmont. The push and pull of regional identity has informed much of the county’s history.

White settlers and the Native Americans who’d arrived centuries before them were attracted to the area that became Gaston County because of its close proximity to the Catawba River. Gristmills lined the riverbanks, and the cotton mills came next. The county’s first mill began operation in 1848 when the county was barely two years old. By the end of World War I, the cotton mills had made Gastonia famous, and the entire industry was built largely on the backs of men and women from Appalachia.

Gastonia’s population quadrupled between 1890 and 1900 as tenant farmers from the North Carolina piedmont and the South Carolina upstate tossed off the shackles of sharecropping for the riches promised by life in the mills. Barkers sent by mill owners converged upon the North Carolina mountains with stories of easy living in the mill villages where housing, education, and independence from the soil awaited rugged individuals willing to make the difficult trip east.

This trip “down the mountain” was often chronicled in story and song, but never so effectively as it was by singer and guitar player Dave McCarn, who was born in Gastonia in 1905 and whose “Cotton Mill Colic” trilogy portrayed the stories he’d heard from former mountaineers who worked alongside him in the mills. In “Poor Man, Rich Man/Cotton Mill Colic No. 2,” McCarn sings about the migration east:

Now I left the mountains when I was a strip,

Never will forget that awful trip.

I walked all the way behind an apple wagon,

When I got to town, people, my pants were a-dragging.

By 1920, World War I had ended and the demand for combed cotton had begun to wane, but people from Appalachia continued making the trip east. What they found was a shrinking job market. As unemployment grew, wages fell and the quality of life in many mill villages worsened.

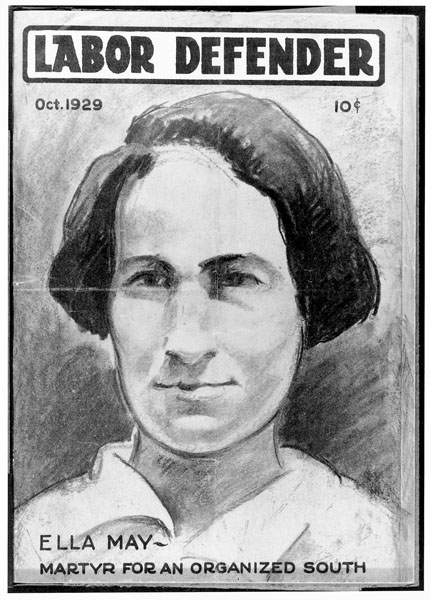

Gastonia’s Loray Mill was one of the mills that shone like a beacon of deliverance for the weary souls who’d spent weeks either in wagons or on foot during the trip from the mountains. Local investors had built Loray in 1900; at the time it was rumored to be the largest mill in the world at 600,000 square feet. In 1929, under the ownership of Rhode Island’s Manville-Jenckes company, Loray’s workers organized a strike to protest wages and working conditions. The strike began on April 1, 1929, and quickly turned violent once the National Guard was called in by the governor. Tensions further mounted when Gastonia’s police chief died after being shot during a raid on the strikers’ headquarters. Over thirty strikers were arrested and charged with murder, but that didn’t quell the violence. In September, a woman named Ella May Wiggins was shot and killed on her way to a rally in support of the jailed strikers. The group of armed men who confronted Wiggins and the others in her caravan were rumored to have been hired by Loray management.

Ella May Wiggins was born in east Tennessee, but she moved with her family to the North Carolina mountains after her father found work in a lumber camp. That’s where she met John Wiggins; the two of them would leave the mountains for the South Carolina upstate and eventually the mills of Gaston County, where John deserted his wife and young family. By the time she was twenty-eight, Wiggins was a single mother of nine children, four of whom had died of poverty-related illnesses. Her story isn’t simply a sad one; it was also incredibly inspiring and, given the era, groundbreaking. She was an active union member, and she was well known for the ballads she wrote about the strike and the plight of workers, several of which would be sung and recorded by Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

Unlike the millworkers from the North Carolina piedmont and the South Carolina upstate, Wiggins possessed neither the racism nor the ideas of gender norms instilled at birth in many of her fellow strikers. This made her incredibly controversial; she challenged the status quo by attempting to integrate the labor union and welcoming African American mill workers, many of whom she lived with in a predominately black community. A few months before her death, she traveled to Washington D.C. to testify before Congress about mill conditions and the challenges faced by working mothers. She was a feminist and a civil rights activist before those terms were in popular use, and, as her murder proves, it made her a marked woman.

In 1935, Loray was sold to Firestone, Inc. and all mention of the mill, the 1929 strike, and the life and murder of Ella May Wiggins disappeared from history.

But that’s all changing. The mill, which had sat unused since 1993, is now being renovated into high-end apartments. What is also being renovated is the legacy of the strike, and with it has come a revived sense of the connection between Gaston County and the Appalachian people who helped build it. This sense of Gastonia’s history goes to show that it was and is someplace, and it proves that Ella May Wiggins was someone then and now.