I didn’t think much of the fall when it happened. It was a typical Whiskey Wednesday, that regular mid-week reprieve from responsibility that a few friends and I enjoy, and we had a New Guy with us. Even though it was his first time skiing with the group, I could tell he was a better skier than any of us. But he caught an edge on an ice chunk when landing a jump and went head over heels. I’d seen worse falls and, after a minute, he got up and skied off the mountain. We did a Shotski back at the van. All was well, but New Guy was feeling progressively worse on the drive home, and by the time we pulled up to his house, he could barely stand. It was time for another Walk of Shame.

Forget about your college years when you trudged across campus in the previous night’s wardrobe. The true Walk of Shame happens after an adventure when you have to walk an injured buddy home and face his wife.

Getting hurt sucks, but it’s not the initial pain that gets you. It’s the aftermath. Most injuries are swift. The pain is on you before you really have a chance to feel it. If it’s severe enough, you’ll go into shock or pass out—both perfectly acceptable coping mechanisms. I spent much of 2020 operating in a mild state of shock, and I highly recommend it.

But the aftermath—that wake of consequences that follows an injury—is the true burden of any accident. Every time I walk a bleeding, broken friend to the door I start to catalog all of the aspects of his life that will be impacted. The baseballs he won’t throw with his kids. The meals he won’t be able to cook. His wife is going to have to pick up the slack. His kids will have to cope with a father that’s a shell of his former self. His work will take a drastic dive in quality because, well, Percocet. This is the true cost of going big and falling short. And this is what makes that Walk of Shame so tragic. Because I know that it’s his wife that will be carrying the burden moving forward. She’s the true injured party in this scenario, and it’s my job to deliver the news. I carry a lot of guilt with me during the Walk of Shame because we’re supposed to take care of each other out there, whether it’s night skiing ice at the local mountain or three nights in the backcountry. We’re supposed to be adults who make good decisions. My wife literally tells me that very thing as I walk out the door to go play with my friends. “Make good decisions.”

Maybe that’s the problem here. I’m a 44-year-old who’s still “going outside to play with my friends.” Shit. I feel an existential crisis coming on. Am I just a great big Man Child avoiding responsibility and making my loved ones suffer in my eternal quest for youth?

Regardless of the underlying root cause, the Walk of Shame happens more often than I’d like to admit. My first Walk of Shame was a double shoulder dislocation with a wicked case of short-term amnesia. A good friend of mine overshot his landing on a table top and hit the ground hard. Like, really hard. He had a 16-month-old at home. And a newborn. I dropped him off in the middle of the night after pulling him out of a small West Virginia hospital and driving several hours home. The two shoulder dislocations were troublesome (he had both arms in a sling), but the amnesia was brutal. Every seven minutes he would come to in the back seat and ask why I was driving his car. And why his arms were in slings. And why his head hurt so bad.

Every. Seven. Minutes.

Also, he didn’t really remember the birth of his second child. That was fun to explain to his wife. My Walk of Shame with the New Guy might be even more traumatic. Six cracked ribs and a lacerated kidney. Of course, we didn’t know that until an hour after I walked him home to his wife and had to go back to take him to the emergency room. He spent two days in the hospital waiting for the internal bleeding to stop.

A lacerated kidney. I always knew Whiskey Wednesday would cause organ damage, but I thought it would happen slowly over a matter of years. I didn’t think it would be so sudden.

Don’t worry, New Guy is recovering just fine. And I’ve been on his side of the Walk of Shame before, hobbling home with the help of a friend after dislocating shoulders and breaking an elbow. Recovery typically moves along swiftly. There’s a grace period after an injury when the injured person has to be remorseful. You’ll say things to your partner like, “Don’t worry, I’m not going to try that again.” Or, “I think the days of charging hard are behind me.” You spend a lot of time talking about “lessons learned.” At first, you mean every word of it—you’re never going to try to send it again—but as the pain subsides the words become empty platitudes meant only to soothe your loved ones. Eventually, you’ll mostly forget about the injury that sidelined you and inconvenienced your family. It’s a natural part of the recovery process, the same way women can gloss over the pain of childbirth and the difficulties of raising babies and convince themselves they should have another.

A couple of years ago, I was on a trip with a pro downhill mountain biker, one of those dudes that rides the Red Bull Rampage, and he was recovering from a wicked collarbone injury. He started listing all of his breaks and contusions over the years, which was extensive and gruesome, and I asked how he handles getting hurt so much. He shrugged. “The more you get hurt, the less you worry about getting hurt. Because you know you’ll recover.”

Maybe. But then again, that pro mountain biker was in his mid-20s and single. He might change his tune when he hits 40 and his wife and kids have to bear the burden of his ‘send it’ mentality. Nothing drives the cost of an injury home like the Walk of Shame.

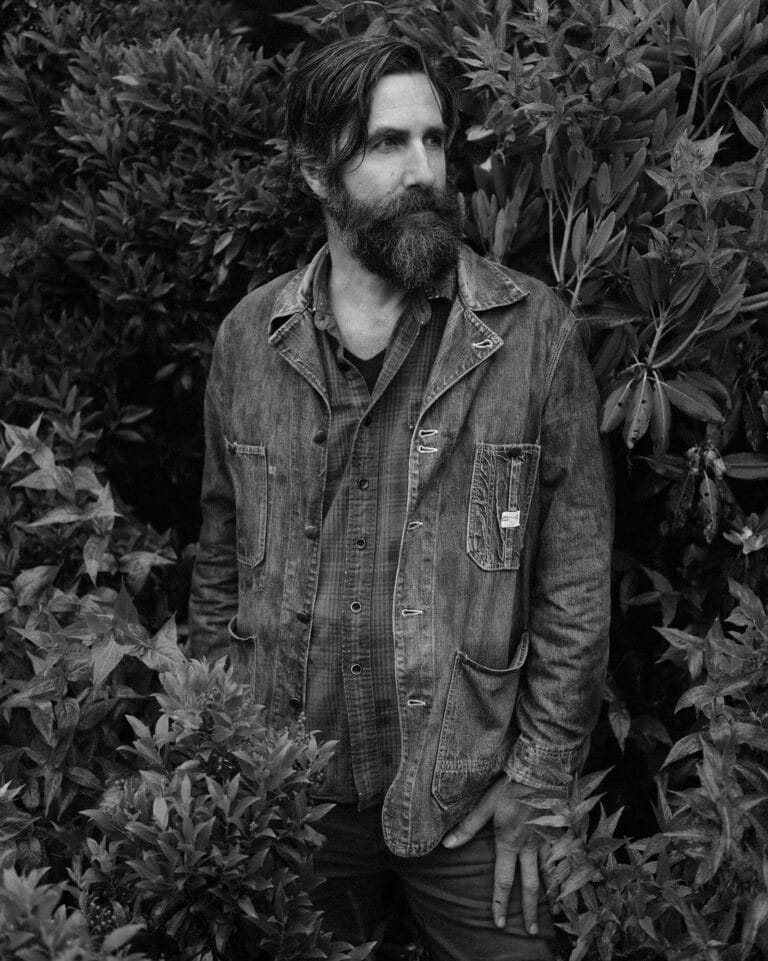

Adventure pursuits have led to the author’s friends suffering serious injuries, including amnesia and a lacerated kidney. Photo by Graham Averill