For 100 years, summer camps have been a mainstay of western North Carolina’s culture. There are over 50 residential summer camps spread among four counties—Transylvania, Henderson, Buncombe, and Jackson—making western North Carolina the most concentrated summer camp area in the world. So what impact have summer camps had on the region? We asked some of North Carolina’s outdoor industry leaders to find out.

In college, Amy Allison was lost. Born and raised in the Louisiana bayou, Allison wasn’t sure what she was looking for, but so far as she could tell, the College of Charleston didn’t have it.

One day, when she was studying for a test in the library, Allison came across a pamphlet that listed summer camps in the area. On a whim, she applied for a camp counselor position at Camp Kahdalea in Brevard, N.C. She was accepted, and after three years of going to school in Charleston and working in Brevard during the summers, she left Charleston for good.

“It was this random thing that definitely changed my life and put me on a different path,” says Allison, now the Marketing Team Manager for Eagles Nest Outfitters (ENO). “Summer camp was the gateway to put me on a track that I knew I wanted to be on but didn’t know how to start.”

Allison eventually finished school at Brevard College. When she finally left her job at Camp Kahdalea after two years of working there full-time, she got a job with Leave No Trace and, later, Landmark Learning. In addition to her full-time gig at ENO, she’s also Chair of the Outdoor Gear Builders of Western North Carolina, an organization comprised of 27 outdoor brands located in her backyard.

If you hang around western North Carolina’s outdoor industry long enough, eventually, you’ll hear a story similar to Allison’s: a child or young adult discovers the outdoors through summer camp, either as a camper or counselor, and their world pivots 180 degrees.

That’s how it happened for Bunny Johns. A competitive swimmer in high school, Johns didn’t have much lined up after graduation. She earned a little money on the side waiting tables in Atlanta, but then she got a call saying she was no longer needed. Almost as soon as she had lost that job, a friend called to offer her another one: teaching swimming at Camp Merrie-Woode in Sapphire, N.C.

Without hesitation, Johns signed on. Founded in 1919, Camp Merrie-Woode is a residential summer camp for girls. When Johns showed up to camp in 1959, Merrie-Woode offered one of the most robust canoeing programs in the region. Through its Captains Program, Johns learned to canoe, and for the next five summers, she never once returned to teach swimming.

She became head of the boat dock and taught hundreds of girls to paddle. Simultaneously, Johns’ paddling career skyrocketed. In 1964 during her last summer at camp, Johns and a handful of camp staff made the first successful descent of section three on the Chattooga. A few years later, she was also on the first descent of the West Fork of the Tuckasegee.

“All of this was new to women at that time,” Johns says. “I mean, it was new for me. I’d been in high school, played basketball, been on the swimming team, but this had a huge impact on me. It’s why I am where I am today and why my life took the course that it did. Camp Merrie-Woode has been the basis for the arc of what has been the rest of my life.”

In 2017, Johns was inducted into the International Whitewater Hall of Fame for her influence on the sport of kayaking. Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Johns won a number of gold medals at the Open Boat and Wildwater Nationals and World Championships. From 1976-2000, she taught canoeing and kayaking through the American Canoe Association while serving as Department Head, Vice President, and eventually President of the Nantahala Outdoor Center (NOC).

Aside from developing a love of whitewater, Johns says working at a summer camp taught her how to work with people of all ages and all backgrounds, a skill she might not have learned otherwise. “I had never been much of a babysitter,” she says.

Now in her late 70s, Johns still hikes and paddles. She even advises Merrie-Woode to a certain extent. She recognizes that summer camps are unobtainable experiences for many middle class and lower income families, but she says there’s no doubt that for those who are fortunate enough to attend or even work at a camp, the lasting impact is tremendous.

“The camps in western North Carolina have put out a diaspora of kids from all over that have more of an appreciation for the outdoors. That camps have continued through so many generations means there must be something to it.”

The Summer Camp Economy

Back in 2011, North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Youth Camp Association (NCYCA) discovered that that “something to it” went well beyond anecdotal observations. The joint study found that residential summer camps poured $365 million back into those four counties’ economies. The 50 summer camps studied additionally created more than 10,000 full-time jobs and $33 million in tax revenues.

The first time NCYCA studied western North Carolina’s summer camp economic impact was back in 1999, when even the camps themselves had little idea as to just how important their establishments were. That year, NCYCA looked at only 40 summer camps, but it was clear even then that their contributions to the local economy were substantial: $96.2 million to be exact.

While only 10% of summer camp staff are hired to work full-time, there are hundreds of seasonal positions available every year. According to the 2011 economic impact study, women make up the majority of the seasonal staff at 69% with 72% of part-time camp jobs held by young people between the ages of 16 and 29. Rockbrook Summer Camp for Girls Whitewater Director Leland Davis says that those jobs have helped churn out industry leaders for decades.

“If you’re talking to somebody who teaches or guides paddling around here, you’re almost guaranteed to find out that they did summer camp at some point,” he says. “There’s a zillion jobs for that so it’s really common for people to try working at camps at some point or another.”

If they’re anything like Davis, chances are they’ll continue working outdoors in some capacity. As a child, Davis was a camper at Camp Arrowhead, now called Camp Glen Arden. He later worked his way through the ranks as a junior counselor, counselor, and program manager. After living on the road for a decade as a full-time kayaker, Davis returned to the camp industry in 2012 to run Rockbrook’s whitewater program. This year marks his 28th season working at a summer camp in North Carolina.

“I would argue that a college-aged person who goes to work for a camp and really puts their heart into it will get more out of that than any kind of corporate internship. They’ll be more prepared to tackle the world in front of them because there are fun times and there are difficult times and you kinda learn how to work through both of those.”

So says Fritz Orr III, the grandson to Fritz Orr, Sr., longtime owner of Camp Merrie-Woode. From the day he was born, Orr was involved in North Carolina’s camp scene. His grandfather and Frank Bell, Sr., founder of Camp Mondamin in Tuxedo, N.C., were old camp buddies from Camp Toccoa in Georgia. The Orr family ran Camp Merrie-Woode until 1978, the year the camp became a non-profit.

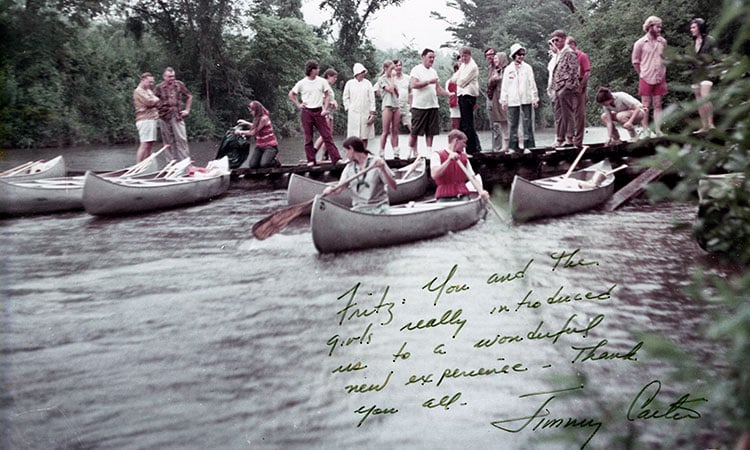

As a teenager whose parents ran a girls’ camp, Orr kept busy by helping build the very boats Bunny Johns and her staff would use on trips. A master paddler himself who accompanied then Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter on that historic descent of the Chattooga in 1974, Orr later went on to compete both in wildwater and open canoe. During the early 1990s, he raced at 28 world championships and, as he says, “put a few national championships in my back pocket.”

Orr has been front and center for all of kayaking’s most notable developments: first in the ‘70s when kayaking made its debut at the Olympics and the film Deliverance hit screens nationwide, and again during the ‘90s when the playboating revolution changed the sport forever. For years, Orr worked with Dagger to develop numerous boats, most notably the RPM. To this day, he continues to hand build canoe paddles (which made him a finalist in the 2010 Garden and Gun Made in the South awards) and teach canoeing at Camp High Rocks.

Everything he’s ever done in life, Orr credits to summer camps. He says the longstanding success of western North Carolina’s summer camps isn’t about location or programming, although both of those are certainly exceptional. He says it’s the level of competency displayed by camp staff that really makes a summer camp great.

“I think today a lot of people would be pretty impressed with the professionalism that is involved in a lot of the Southeast’s camps,” he says. “The bar that the directors and the full-time staff hold up is very, very high. There are a lot of moving parts to get right, and there are a lot of camps here getting it right.”

That’s something Landmark Learning founder Justin Padgett has also witnessed, especially within the past decade. When Padgett started Landmark Learning in 1996, camps were one of the organization’s main clients. Over the years, he’s been impressed to see the commitment western North Carolina’s camps have made toward building competent staff in-house and credits that to the camps’ high staff retention rates.

“A camp professional is more of a professional,” he says. “You need a deeper and stronger resume than you used to. You have to be better than just a good person to be hired at these camps. You have to have the skills to back it up.”

Padgett and his wife Mairi also went to summer camp, though not in western North Carolina. Both of their children go to summer camp—this year, their daughter will be attending her third summer at Camp Green Cove while their son will be heading to Camp Mondamin for the first time. Padgett thinks it’s this tradition—of parents going to summer camp and then sending their kids to summer camp, and so on and so forth—that has absolutely turned western North Carolina into a major player in the outdoor industry.

“The camps are strategically integral in the whole development of our economy in western North Carolina,” he says. “It was really the camps that started it. Outward Bound wasn’t even here until 1965. They weren’t even around when Camp Mondamin was rocking the house. Camps were the ones creating these trip leaders and putting up routes at Looking Glass and figuring out these waterways. Now they’re a lobbying power. They’re talking to lawmakers and legislators saying look at these numbers, look at this employment, look at the economic development in an area that is generally economically depressed.”

North Carolina isn’t ignorant of the fact that the state’s outdoor industry is an economic machine supporting over a quarter-million jobs. Earlier this year, the state hired an Outdoor Industry Recruitment Director for the sole purpose of promoting and attracting outdoor industry businesses.

But arguably more important than bringing in the big bucks, summer camps have proven instrumental in another facet of North Carolina’s outdoor landscape: conservation.

Keeping WNC Green

Representative Chuck McGrady was executive director of NCYCA at the time of the 2011 summer camp economic impact report. The former owner of Falling Creek Camp in Zirconia, N.C., McGrady is also a republican, camp advocate, and staunch conservationist.

He’s reached across the aisle on a wide range of issues, from coal ash to beer bills, and helped bring major outdoor initiatives, like the protection of DuPont State Recreational Forest, come to fruition. McGrady acknowledges that his own time as a camper at Camp Sequoyah was fundamental in instilling the value of the area’s outdoor resources. He’s made it his life’s work to keep those resources the same as he experienced them all those years ago.

“People wonder why Henderson County is as green as it is. There are two reasons: one is that we have a strong agricultural economy, but the other piece of it that people don’t know is these summer camps that are scattered all over the place, sometimes sitting on several thousand acres. Those lands are not developed. They’re kept just for mountain biking and backpacking. There are huge parts of the county that are preserved by the summer camps.”

For areas of western North Carolina not protected by summer camps, it’s former campers and camp staff who are doing the legwork now to defend those places most in danger. The Nature Conservancy’s North Carolina State Director Katherine Skinner is one of those tireless champions. An alumna of Camp Green Cove, Skinner says the camp left such an impression on the value of nature that many of the camp’s out-of-state alumni will donate significant sums of money to The Nature Conservancy’s North Carolina efforts.

“The Blue Ridge Mountains are very special, and we’re lucky to have them,” she says. “We need to keep them the way they are. When I went to summer camp, it never dawned on me that they would ever be anything but the way they are, and now I see the trouble they are in.”

In the early 1990s, Skinner headed efforts to purchase a stretch of the Green River from Duke Power Company. It was the section Camp Green Cove used to teach campers to paddle. The Nature Conservancy also protected the headwaters of the Tuckaseegee River, another important river site used by many camps in the region.

It’s clear that summer camp taught Skinner and many others one very fundamental theory that has been cited by environmentalists since the dawn of Thoreau: you can’t love what you don’t know. For Skinner and her fellow camp compadres, they know western North Carolina’s rivers and forests inside and out, and they remain ready to rally in their defense.

Coming Full Circle

At their core, summer camps are laboratories for self-discovery, creativity, and resiliency. Numerous studies out of the American Camp Association have proven that summer camp experiences increase self-esteem, conflict management, leadership, and independence in children.

In addition to the environmental awareness camp instilled in Skinner, her years at Camp Green Cove also showed the potential women specifically could achieve. Skinner was a camper in the 1960s and ‘70s, a time when women were just starting to elbow their way to positions of authority.

“I didn’t know what I was looking at at that age, but looking back on it, you saw women running things at Green Cove. Women were not in leadership positions in the town I grew up in or generally in the outside world,” she says. “My generation sorta broke through that but still, you were encouraged to learn, but in subtle ways you were shown your place. You weren’t shown your place in summer camp. You were taught that the world is your oyster and you are a pearl and you could do whatever you set your mind to do.”

Watershed Dry Bags founder Eric Revels similarly picked up on that limitless possibility when he was a camper at Camp Mondamin. As a child growing up in New Orleans’ French Quarter, Revels had no idea what lay beyond the city until he arrived in western North Carolina with Robert Danos, his childhood friend and now Program Director of Camp Mondamin.

“It was a life-changing thing for me,” he says. “People ask how I got into whitewater kayaking and starting a paddling gear company being from New Orleans, and it’s absolutely my time at Camp Mondamin. The camp experience changed my entire career and my entire life. I don’t know what I would have done without it.”

In fact, Revels can pinpoint the exact moment at camp when his worldly views about the future were turned upside down. He was on an overnight paddling trip on the Chattooga River with John Dockendorf, who later founded Adventure Treks and Camp Pinnacle. Everyone was sitting in a circle, discussing their futures, when Revels was asked what he wanted to do when he grew up.

“I think I’ll be a doctor, maybe a lawyer,” Revels said. They make good money. In reality, Revels didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life. Dockendorf, who likely sensed that, told him passion, not money, was more important. And that was it, the moment a lightbulb went off in Revels’ head.

“That really got me thinking,” he says. “It was the first time anyone said something like that to me. Your mentors at camp, they’re like gods to you. They’re only college kids but from the perspective of a 10- or 12-year-old, you totally look up to them.”

One of those larger-than-life mentors for Revels was Lecky Haller, a Baltimore-bred Olympian. Haller, who had also gone to Camp Mondamin and later worked as a counselor there, played lacrosse for 16 years throughout high school and college, competing at the highest level possible.

He eventually switched to competitive canoeing, the basics of which he had learned all those years ago at Camp Mondamin. He and his brother Fritz won the world championships in tandem canoe in 1983, which launched Haller into a 20-year career of competitive paddling.

In all, Haller won nine medals at the World Cup stage, four medals at World Championships, and twice represented the U.S. in tandem canoe slalom at the 1992 and 2000 Olympics. So when he showed up to paddle with the Mondamin campers, it was no wonder he was granted legend status.

Despite all the medals, Haller, who now directs the Asheville School’s athletics department and still teaches paddling at Camp Mondamin, thinks the most important thing camp ever taught him was the reward of the activity, not the podium.

“The reward was what you did, the trips you took,” he says. “There were no awards or ribbons and that’s still the way it is at Camp Mondamin. That’s a pretty good lesson. You don’t need something outside of that, something dangling in front of you. The adventure is the reward.”

Haller, like Leland Davis and Fritz Orr and Bunny Johns, have come full circle in their respective summer camp careers: first as camper, then counselor, now consultants and program directors at the very camps they once enjoyed. That’s how it goes here—forever friendships are formed, life-altering memories are made, and those blissful three months of the year live on generation after generation.

“The camps don’t seem to change that much,” says Haller. “Camp Mondamin has been in the same family for three generations. My memories of it are the same now as they were back then. I’m fortunate to be able to live those same things and to take these kids on the same trips I took 50 years ago. It’s cool that way to be able to show them what I saw.”

It’s family weekend at Camp Mondamin, the last family weekend the camp will ever host. Eric Revels and his family are posted up on Lake Summit’s shores. His son, then only five years old, wants to be just like his dad. He wants to be a kayaker. But per Mondamin rules, any camper who wants to kayak must be able to swim for 30 minutes.

Revels’ son is too young to be a camper yet, so he only has to swim for 10 minutes. But still, at age five, swimming continuously for 10 minutes is no small feat. His son tries, and fails, once, twice, three times. He staggers out of the water, clearly downtrodden but not yet defeated.

Revels agrees to swim with him on his fourth try. The father-son duo wade back out in the water and begin to swim. Suddenly, the sky clouds over. Rain begins to fall in heavy sheets.

“At this point he is just grittin’ it out, practically crying. We’re in this downpour swimming around in circles. And finally he passed it on his fourth try. I was so stoked. That’s what that camp is all about. Here’s an obstacle, overcome it, but you have to find what’s within you to do it.”