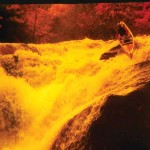

Save for your own heart thudding behind your chest, the only noise you can hear is that of a thundering freight train. It’s a low rumbling, a guttural churning. It’s the sound of unseen whitewater, of hundreds of cfs (cubic feet per second) of surging current charging toward a horizon line before dropping off into the void. Steep canyon walls rise from the river’s edge, boxing you in, committing you forever downstream.

The late afternoon sunlight filters into the gorge, but soon it will be gone. You and your partner stare at the lip from the safety of your cockpits several yards upstream. An almost foreboding sense of dread coupled with the enticing allure of the unknown tempts you to carry on. The only assurance you have that anything even exists beyond the river’s edge comes in the form of mist spraying intermittently into the air. Aside from that, you know nothing of what lies ahead.

To some, kayaking at even its most basic level seems counterintuitive, reckless, a sure sign of a death wish. At first blush, the sport may certainly seem that way—after all, you are strapping yourself into a plastic boat and hurling yourself down a natural force that carves out mountains, for Pete’s sake. Undoubtedly, kayaking is not everyone’s cup of tea. But the media coverage that the whitewater community, and the adventure sports world at large, receives does little to resolve any misgivings about outdoor recreation.

The news celebrates the dramatic and mourns the traumatic. Sensationalized reports like that of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s record free climb of the Dawn Wall or the tragic unveiling of kayaker Shannon Christy’s death on the Great Falls of the Potomac River lead the public eye astray, to the idea that the world of adventure is either awe-inspiring or foolishly dangerous and nothing in between. And the adventurers themselves? Well, they can be heroes one day, adrenaline-crazed junkies the next.

But what about you and your partner, sitting there above a rapid you’ve never run before? Maybe it’s the first time any human being has seen this river from the cockpit of a kayak. Or perhaps you’re just another paddler, one of the hundreds who will navigate these same waters during the season. You’re not out there for the fame and glory of it. You’re definitely not out there with a death wish—actually, you’d prefer to make it downriver alive so you can paddle again tomorrow.

So why do you do it? Why spend your free time dancing with danger, risking life and limb for an activity of no apparent societal value while cozy couches and the latest Netflix releases sit unattended? What is it about kayaking, about riding, about climbing, that beckons to you, that begs and pleads then outright demands you to ditch work early and head for the mountains? What is it that keeps you coming back for more even after the worst of swims? What is it?

French philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau called it l’homme sauvage, the wild man that lies beneath our civilized exterior. English explorer Sir Richard Burton blamed it on “the devil [that] drives.” Scientists worldwide have attributed a heightened presence of it in humans that carry the 7R variant of the DRD4 gene, a dopamine-receptor in the brain that elicits restlessness and encourages novelty-seeking behaviors.

Whatever you want to call it though, we all have it. It’s what makes us climb up trees as children, date new people as teenagers, and take jobs and move away as adults. It’s what makes us fire up the rapid we always used to portage and charge the cliff we normally sneak. It’s the call of the unknown, the longing for the land of Beyond, but it’s about time we asked ourselves—will it ever push us too far?

Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

In 2009, kayaker Tyler Bradt soared 77mph over the lip of Palouse Falls in Washington State. When his boat hit the water, it disappeared beneath the falls’ pummeling for nearly seven seconds. He eventually surfaced, still inside his boat and with a broken paddle in hand, but surprisingly he was unharmed and, it should go without saying, stoked at having set the record for the tallest waterfall ever run in a kayak. It was 189.5 feet in height.

Bradt’s accomplishment was considered groundbreaking by some, insane by others. No one at the time knew if the human body could withstand such an impact and live to see another day, and no one’s topped that record since. At 167 feet, Niagara Falls would have come in at a close second, but Red Bull paddler Rafa Ortiz backed away from the challenge in 2013 after three years of meticulous planning and preparation for the first descent.

“I walked to the drop like I’ve done with many waterfalls in the past, looking for that last positive feeling,” Ortiz said on social media afterwards. “It wasn’t there.”

While Bradt and Ortiz’s vertical exploits represent the fringes of the sport nowadays, it’s only a matter of time before running 100-plus-foot waterfalls becomes mainstream. Just 30 years ago, the kayaking community would have never considered running a 100-footer in a boat (and surviving it) as even a remote possibility. The early days of the sport were focused more on slalom paddling and downriver races. Kayaks were 13 feet long, homemade, and, consequently, easily breakable. Impacts from plunging over a waterfall like Palouse would surely result in serious injury if not death.

But that doesn’t mean the early pioneers of the sport weren’t lured away from the slalom world by the call of the unknown, that tantalizing prospect of possibility. In fact, had it not been for renegade paddlers from the ‘70s and ‘80s who crashed their awkwardly long boats down steep creeks no one had ever seen before, Bradt might never have developed the skills or found the courage to buck up and huck Palouse Falls.

A lot has changed within the sport of kayaking in just a few decades. Between boat redesigns, new moves and skillsets, and beta galore on rivers and creeks previously deemed unrunnable, the paddlers of today are presented with a new challenge—what next? And more importantly, will the risk of taking that next step be worth the reward?

To help visualize just how far the sport has grown, and to provide some insight into the paddler’s psyche, I talked with six boaters, past and present, who have tread that line of possibility, battled risk for reward, and helped to progress the world of kayaking in the Blue Ridge and beyond.

Charlie’s Choice

It was the spring of 1972. Pennsylvania born-and-raised Charlie Walbridge sat in his boat below the class IV rapid Bastard on the Upper Youghiogheny River, trembling, barely able to pull his skirt over the cockpit.

Walbridge was just a 20-something-year-old at the time with a c1 (that’s a one-man canoe with a covered cockpit) and a wild hair. He was a seasoned paddler who frequented the rivers of western Pennsylvania and the northern parts of Virginia and West Virginia. Having paddled extensively for the past five years, Walbridge was well versed in the ways of whitewater.

But that day, Bastard got the best of him.

“I got run off the Upper Yough,” Walbridge remembers. “It was my first time. I was shaking so hard I couldn’t put the skirt back on. That’s when I knew I didn’t belong there.”

Walbridge decided to walk out (hence the rapid’s name, Charlie’s Choice). Keep in mind this was the early ‘70s. Runs like the Upper Yough and the Upper Gauley, now still considered classics but by no means legitimate class Vs, were among the stoutest of the stout in the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic. Walbridge’s decision was respectable, not cowardly.

Though he would later take part in some of the first paddling expeditions to navigate the waters of the notoriously steep upper section of the Blackwater River (before the flood of 1985), Walbridge never had his mind set on chasing first descents or making a name for himself among the paddling community. He was in it for the sheer enjoyment of the river.

“We were all just trying new things out,” he says. “That was the fun of it. There’s nothing better than going down a river that you don’t know and that there’s not very much known about it. It’s as good as it gets.”

Walbridge never stopped paddling. Even at age 67, he still runs the class IV+ Big Sandy (so long as it’s under six feet) and stays involved with the boating community at large. For over 40 years, Walbridge has written accident reports of whitewater-related incidents and has even served as the Safety Chair for the American Canoe Association (ACA) and American Whitewater (AW). In addition, he has helped to develop swiftwater safety curriculum for ACA and oversees whitewater-canoeing instruction.

There’s no doubt about it—Walbridge has seen some big change come to the paddling world. So what does he think about its future?

“People are clucking and shaking their heads at the hot paddlers today who are running waterfalls, but I remember people clucking and shaking their heads at us for playing at Pillow [on the Upper Gauley]. The young guys make me nervous, but that’s their job. We made the old guys nervous when I was in my 20s!”

[nextpage title=”Next Page”]

The Will to Survive

“John, you could die right now.”

Those were the last words John Regan remembered telling himself before he slipped into an adrenaline-fueled survival mode. It was 1989, and Regan had agreed to show his friend down the Upper Blackwater in West Virginia, a class V stretch of whitewater known for its heinous sieves and big boulders. He was paddling a 13-foot slalom boat, which he preferred, he says, because “plastic boats at the time weren’t high performance—they were dogs.”

But it was precisely the boat’s low volume and unwieldy length that got Regan in a position that had just recently killed his friend and fellow paddler: a vertical pin. Regan was trapped, upright, quite literally between a rock and a hard place. Somehow, Regan managed to maintain his air pocket while he shifted his weight and maneuvered the boat out of the predicament. The next rapid down, however, he pinned himself again above a significant drop. His nerves were shot.

“I’ll never forget, my buddy was there, and he got me out of the pin and immediately slapped me across the face and said, ‘If you can’t handle this we’re walking outta here right now,’” Regan remembers.

That slap back to reality was all it took, and the two successfully finished the run, but Regan remained acutely aware of the risk that inherently came with the sport.

“I’ve lost 30 friends through my kayaking career,” Regan says. “There’s no rule or reason, no why or who. Anybody can die no matter how good you are, but we wouldn’t be pushing the limits if we didn’t have people that seek that balance of risk and reward.”

Soon after the Upper Blackwater run, Regan ditched the slalom boat and picked up a Prijon T-Canyon, one of the early plastic prototypes, and did just that—he pushed the limits. From the North Fork of the Blackwater to the Upper Otter, Overflow Creek, and Red Creek, Regan knocked off first descent after first descent throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

He’s no stranger to mishap—adversity has played quite a part in his decades of kayaking and snow kiting and backcountry skiing. But he also knows what it means to see potential in something seemingly impossible, to go against the grain, to trust your gut and roll with it.

“It’s not for the glory. It’s not for the picture. It’s a personal test, ” he says. “To see what these young guns have accomplished, you gotta believe that the next generation is gonna accomplish more. I mean, just think about Dane Jackson’s kid! What’s next?

The Forbidden Kingdom

Wick Walker never took ‘no’ for an answer. ‘Can’t’ was simply not in his vocabulary. It was a mentality that had served him well all his life, so much so that it’d helped him gain a spot among the United States whitewater canoe team at the World Championships of 1965, 1967, and 1971, as well as the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

So when the National Park Service personnel patrolling the Great Falls of the Potomac told Walker he couldn’t make the first descent of those yet-unrun rapids that straddle the Maryland/Virginia border, Walker smiled politely, then went and grabbed his gear.

“They were hell bent on stopping us,” he remembers. “Of course, that made it that much more tempting.”

On a Sunday morning before dawn, Walker, local legend and longtime friend Tom McEwan, and their mutual friend Dan Schnurrenberger put in on the Potomac River and paddled a mile and a half upstream. It was 1976 and by the time park service patrollers arrived at their post just a couple hours later, the three men had already checked off the first descent of what would become one of the most iconic class V runs in the Mid-Atlantic.

“That run took three years of preparation,” Walker says. “We proved you could build the skills to do something that looks darn near impossible.”

After the Great Falls success, Walker became hungry for more. He was part of the second crew to run the Meadow River and Upper Blackwater (pre-flood) in West Virginia, one of the first to navigate the Linville Gorge (though not in its entirety). He lived in Europe for a number of years, paddling everything he could in the Alps. But all the while, his eyes were set on another goal: the forbidden kingdom of Bhutan.

“Nobody in, nobody out,” Walker says of Bhutan’s power-hungry government. “There had been no climbing expeditions, and ours would be the very first paddling expedition. That’s why it was such a super fun challenge.”

Walker and his crew of five spent four weeks in Bhutan in 1982, racking up first descents on the Paro, Thimphu, and Pho Chu Rivers. The experience did little to satisfy Walker’s need to explore. He continued to kayak throughout North America, Mexico, and Europe and eventually landed in Pakistan by way of his career as a military advisor. He’s experienced a number of traumatic incidents on the river, lost friends and fellow paddlers, found himself caught in rising flood waters, and blacked out from a lack of oxygen while finagling his way out of a vertical pin, but his dedication to pushing the boundaries of the sport remained tried and true throughout his paddling career.

“I am astounded every time I see what some of these guys are doing these days,” he says of the current generation of paddlers, “but on the other hand, we did think that we were just at the very beginning, that all sorts of neat stuff was gonna be done.”

It’s Assumed

Dark was nearing. The clouds overhead had opened up into a mid-winter storm, pelting sheets of ice onto the river below. It was December of 1987, and Lee Belknap and his paddling partner Victor Jones stood to the side of the Horsepasture River in North Carolina, contemplating their next move.

Behind them rose the steep canyon walls, sheer 60-degree slopes that were now slick from frozen precipitation. Ahead of them? A series of cascades dropping over 700 vertical feet in less than a quarter mile, the infamous Windy Falls.

“Our only option really was to do this 35-foot rappel, which we’d have to do with my throw rope,” Belknap remembers. “I know it was 35 feet because it used up half of my 70-foot throw rope.”

Though the two had started the day early with every intention of finishing the first descent of the Horsepasture down to Lake Jocassee, the fact of the matter was that, unless they wanted to paddle their half-frozen, exhausted bodies through the night to the lake, they would need to hunker down and finish out the run the next morning. Fortunately, the pair was prepared with bivouacs and camped out on a surprisingly level spot just two-thirds of the way through their portage of Windy Falls.

“Our wet gear started freezing about 10 that evening,” Belknap says. “We had to improvise heavily but we were able to keep warm. I’m not sure what Victor thought about it, but I slept like a baby.”

With a fire roaring and a full moon lighting the rim, Belknap, actually, couldn’t have been happier. Though that would be his first and last time down the Horsepasture by boat, Belknap never forgot the sound of the thundering falls luring him to sleep and that quiet satisfaction of being surrounded by wilderness, a feeling that outweighed any sense of bravado he might have felt at being the first to descend what would become a classic class V run in the Southeast.

“I just love the exploration,” Belknap says, “but I spent 25 years playing lifeguard and I can’t tell you how many people I’ve saved.”

Having served as Safety Chairman for American Whitewater for 12 years and kayaked around the country for three decades, Belknap has seen it all. One of his most stressful moments occurred on the Chattooga River when friend and fellow paddler Rob Baird found himself pinned underwater at Hydroelectric Rock. Baird went without oxygen for nearly seven minutes.

Belknap and his crew didn’t waste a single second, though. Belknap hopped out of his boat and into the water, working quickly at extracting Baird’s body. When he came free, the other paddlers began resuscitating him and making plans to execute an evacuation. Thanks to their valiant efforts, Baird would go on to make a full recovery.

“Whitewater is an assumed risk sport,” Belknap says. “You assume there’s a risk, and part of the sport is to figure out what those risks are and how to manage them. I spent a lot of time doing stuff people thought I shouldn’t be doing, but kayaking is a sport of risk managers, not risk takers.”

Kids These Days

Kids These Days

With shoes like that to fill, it’s hard to imagine that the sport could go any further. The heyday of paddling was, debatably, the 80s and 90s when kayakers were building new boats, stomping steeper runs, and creating today’s top whitewater-specific gear manufacturing companies in their garages.

The young guns of today have it made. They don’t have to build their own boats or suffer through the cold in their rain jackets and heavy wool—they have high performance drysuits and pogies and large-volume, lightweight creek boats made from durable plastic. They don’t have to wonder what lies around the river’s bend, for someone has already been there, already seen it and photographed it and put up reports of it on Boater Talk and American Whitewater. Kids these days get to sit back, relax, and ride the currents of blood, sweat, and boat pins laid down by the pioneers before them.

That is, of course, unless they have it, that fire-in-your-belly, call of the unknown that can’t be answered, can’t be satisfied by simply following in the flow of their whitewater forefathers. As T.S. Eliot once wrote, “Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far it is possible to go.” Geoff Calhoun and Pat Keller are among those who are willing to risk just that.

“It’s such an awesome experience to be doing something people didn’t know if you could do or not,” Maryland-based paddler Geoff Calhoun says. “What hasn’t been done around here is really low volume manky stuff that requires huge amounts of rainfall.”

In 2010, Calhoun got that huge amount of rainfall and knocked off the first descent of Jordan Run in West Virginia, a decent-sized drainage with a boxed-in gorge and a sizable 30-foot waterfall. Setting out on Jordan Run required more than just a hearty sense of adventure and class V creeking skills—it required total commitment.

“I was scared,” Calhoun remembers. “I get nervous about doing big things, but we scouted the waterfall diligently. It was either run it or do a pain-in-the-ass portage.”

Calhoun and his paddling partner decided on the former, both successfully running the entirety of Jordan Run and the falls twice in one day. Calhoun’s since revisited the creek and discovered that, despite having paddled it a few times now, “there’s still a bit of mystery around it,” something he says, that makes him respect the river that much more.

Calhoun never imagined racking up a first descent. Jordan Run was really a matter of being in the right place at the right time and knowing the right people. But for Asheville-based paddler Pat Keller, first descents are his bread and butter.

Linville Falls, Toxaway Falls, Cane Creek Falls, Ozone Falls, Shining Rock Creek, Noccalula Falls, Laurie’s Falls, Upper Creek—the list goes on and on, and these are just a handful of Keller’s first descents in the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic, but this guy’s been around. He’s also joined Red Bull athlete Steve Fisher on a first descent of the Hanging Spear Falls Gorge on New York’s Opalescent River, a run that drops over 950 feet in three quarters of a mile. He’s been the first to huck the 70-foot Big Brother Falls on the Valser Rhein in Switzerland and the 65-footer Aldayjarfoss in Iceland. He’s put kayakers to shame year after year at the Great Falls Race on the Potomac and the Green River Race in North Carolina, kickflipped Oceana on the Tallulah, and even spearheaded the creation of a new boat and new racing class specific to the Green River Race. He’s done all of this, and more, before he’s even hit the big 3-0.

It’s no wonder, then, that Keller was voted Canoe and Kayak Male Paddler of the Year in 2014. But behind all of the first descents and record runs, Keller’s certainly dealt with his fair share of bad days.

“When I was 15 I watched my best friend drown in British Columbia,” Keller says. “The risk is not lost on me. If I feel like I’m trying to talk myself into something, I won’t do it.”

Keller’s a competitive type, there’s no doubt about that. Having been raised in a river loving household with a background in slalom racing, Keller has spent the better part of his life learning how to go bigger and faster. But Keller has it, that need to explore, the compulsion to push, to not just wonder what’s around the bend but to put body, blade, and boat there and see for himself.

“It’s just that primal desire to explore combined with the satisfaction of using your body as one mechanical system,” he says, “because part of living is exploring. Water is such a powerful thing. It moves boulders, it changes mountains. To be able to dabble in that power is pretty freakin’ amazing.”

Keller lives and breathes the world of whitewater, and if there’s anyone who can comment on the future of the sport, it’s this guy. With the advent of kayaking schools, safer and more dependable boats, and more accessible beta, the popularity of the sport has blown through the roof. Kayakers are firing up class IV-V rivers in their first year of paddling, something that would have been practically unheard of back in the days of Walker and Belknap. But is it all bad, or is there a silver lining to all of this gung-ho energy?

“Do I think we’ve reached the limit of what can be run in a kayak? Absolutely not. Are we pushing the limits of possibility? Sure,” Keller says. “Waterfall running has a ways to go before we reach the ragged edge, but to ponder what we as humans can set our minds to and then do, it’s amazing.