Who was Elisha Mitchell—the man who first summited the highest mountain in the East—beyond the short, terrible span of his final moments?

In April, I walked up the ramp from the parking lot at North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell State Park to the mountain’s summit, as have countless visitors before me. I wanted to find out more about the mountain’s namesake—Elisha Mitchell, the 19th-century professor who died attempting to prove this mountain was the highest in the East.

At the summit of Mount Mitchell is a tower with a plaque that reads:

Elisha Mitchell (1793 – 1857)

Scientist and professor. Died in attempt to prove this mountain highest in eastern U.S. Grave is at summit. 285 yds. S.

When you arrive at the observation deck at the mountain’s top, there’s another marker for Mitchell, this one set into the side of the stone tomb where his body now rests:

Here lies in the hope of a blessed resurrection the body of the Rev. Elisha Mitchell D.D. who after being for thirty-nine years a professor in the University of North Carolina lost his life in the scientific exploration of this mountain, in the sixty-fourth year of his age.

June 27, 1857

As I looked at the tomb, I thought about the professor, two months shy of his 64th birthday, wandering these mountains over 150 years ago.

Mitchell was trying to prove that he’d found, measured, and climbed the highest peak in the East—despite rancorous counterclaims by Congressman Thomas Clingman, a former student of Mitchell’s, who maintained that he hadn’t.

The debate between the two public figures played out for more than two years, and Mitchell set forth to lay to rest any questions about the legitimacy of his assertion. He died in the effort.

When he fell to his death on June 27—and that day is an estimate—he was heading to the cabin of Big Tom Wilson, a famed mountaineer, hunter, and expert guide who lived near what prominent 19th-century geologist and geographer Arnold Guyot called “Black Dome” when referring to the mountain.

The name Guyot chose is telling of the debate. He labeled it such in an effort to avoid referring to the peak with Clingman or Mitchell’s name attached to it—a mid-19th-century form of political correctness. It’s likely that locals rarely referred to the mountain by name at all—the seven tallest peaks in the Black Mountain Range, of which Mount Mitchell is one, vary in height by only 140 feet.

The professor was seeking Wilson’s assistance in exploring the area and securing his claim, having grown weary of a long debate with political overtures. Ultimately, Wilson assisted in locating the professor’s lifeless body, found floating in a pool of water at the base of what is now known as Mitchell Falls.

Wilson deduced that the professor was crossing a creek above the 25-foot-high falls, and that night had fallen. The conclusion drawn by Wilson was that the professor struck his head as he tumbled down the falls and that he then drowned in the pool below. There is also a mention by an eyewitness to the recovery of Mitchell’s body of “a slight wound on the head, caused, I think, by falling against the log…that leans against the torrent’s channel.”

Wilson discovered Mitchell eleven days after he died, and did so with his own small group after larger, formal searches had been called off.

The pocket watch that Mitchell bore is stopped at 8:19, with an assumption by Wilson that this marked the time of the professor’s death. Saturday, June 27, was the assumed to be the date of Mitchell’s death based on a diary found on his body that includes an entry from earlier that evening. Both the time and day strike me as estimates made concise to imbue a dark, unseen tragedy with some measurement, and in turn, the small comfort that comes with knowledge and understanding.

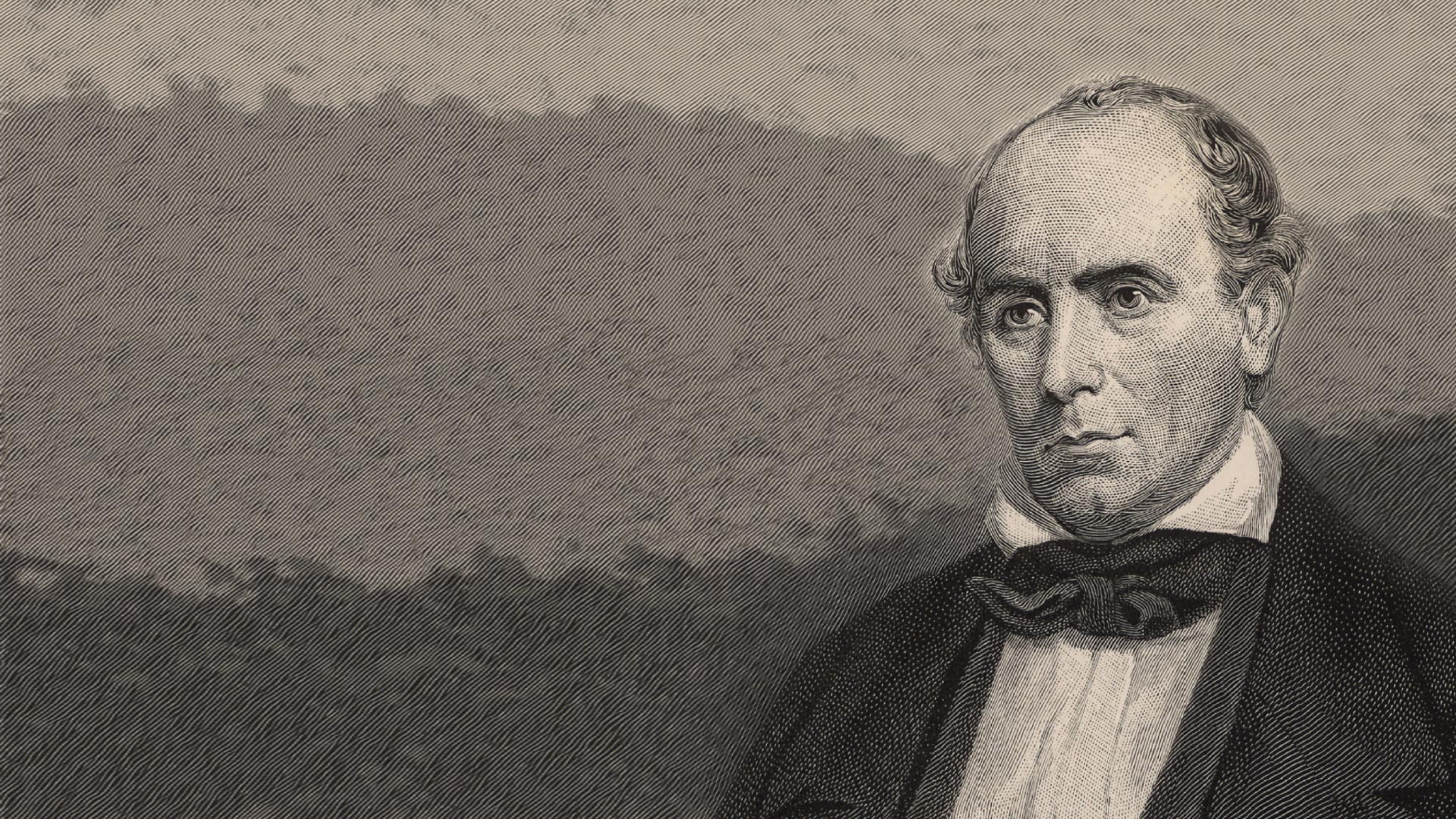

Who was Mitchell beyond the short, terrible span of his final moments? The park museum largely conveys the story above, but despite its recounting, Mitchell remained to me thoroughly two-dimensional, and his life only defined by it abrupt ending. The drawings that exist of him are variations on a theme: a balding man, with wisps of hair curled around his temples, a formal collar and tie, and a look away from the portraitist that obscures insight into his eyes and in turn the person.

On this visit, a thick bank of fog cloaked the mountain and rolled up its sides as if blown skyward by an unseen fan from below. As I descended the ramp, I headed off onto a trail tucked beneath the summit. It was clear treading on the path, but quickly thickened into a riot of fallen dead trees, rock outcroppings, and underbrush once I veered from it. If nothing else, the detour afforded me a glimpse into how limited Mitchell’s views must have been, even at these heights, and how slow his progress.

Coming out of the woods, I walked the length of the parking lot to my small pickup. A young couple pulled up into the lot—the only other car there that day—and sprang out with a cellphone held aloft, pointed down at them. They ran in circles waving and sharing to their audience the splendor of this lofty, mist-shrouded, asphalt parking lot. They then hopped in their car and speed back down the mountain. I smiled and thought that—ironically—his eponymous mountain may not be the best place to better come to know Mitchell the man. It began to hail.

I later do some reading to fill out the dimensions of the professor. He was born in Connecticut in 1793, and graduated Yale in 1813. He began teaching at Chapel Hill in late January, 1818, and was joined on his journey southward by fellow classmate Denison Olmsted. Both took up professorships at UNC, then called North Carolina University, with Mitchell teaching mathematics and “natural philosophy,” a precursor to today’s physics.

Mitchell’s wife, Maria North, arrived in Chapel Hill a year later in 1819. At the time, the town was an outpost in an endless wilderness of oaks and loblolly pines, a cluster of some half-dozen university buildings and 40 houses comprising the village. It was a small, steadfast clearing in a sea of trees with its purpose the schooling of roughly 100 young men. The hope for their education, and one held by Mitchell, was to strike back the dark uncivility that in mid-19th century academic minds often accompanied untamed wilderness.

With that backstory in place, in May I drove east 220 miles from Asheville to Chapel Hill to help picture Mitchell’s time there. At the Wilson Library at UNC, I quickly find the pocket watch that has only grown in its fascination for me since I first heard of it. It’s under a glass case, and now festooned with a faded black ribbon marking its dark place in Mitchell’s history.

From there, I head to the reading room and pore over handwritten accounts of the professor and his peers, some dating back to the 18th century. It is as thrilling as it is often indecipherable, the ink and quill of the age forcing a slanted cursive that readily lends itself to misinterpretation.

I learned that Mitchell was no religious firebrand, though he would bend the ear of a student on theological matters when the opportunity arose. But his tranquil demeanor and infinite patience were celebrated by many students and colleagues.

In 1835, Mitchell had used barometric observations to measure the heights of the Black Mountains, and he determined that one peak was the highest mountain in the East. Nine years later, in 1844, Mitchell decided to confirm his findings on foot as part of his general ongoing work of surveying the western part of the state. It was on this trip that Mitchell summited what is today’s Mount Mitchell.

But then in the early 1850s, one of Mitchell’s former students, Thomas Clingman, claimed that another peak was highest, and that he had summited it first. Clingman was a prominent attorney and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. His counterclaims were wide and varied, and delivered with the oratory and written skills of a congressman and attorney. The debates between Mitchell and Clingman were often vitriolic, which ultimately prompted Mitchell to return to the mountain to prove the accuracy of his measurements in his last fateful journey.

In the year following Mitchell’s death, a host of supporters corroborated his 1844 trip to the summit and confirmed his mountain was the highest. Part of this was proven when Big Tom Wilson—by the late 1850s a national celebrity for his mountain acumen—re-created the 1844 journey of Mitchell and brought experts to the point that is now the summit of Mount Mitchell, and known to be 6,684 feet.

I’m most struck by the letters that poured into David Lowry Swain notifying him of Mitchell’s death. Swain was the former North Carolina governor who was by then president of UNC. The notes uniformly convey a despondency about the professor’s death that does help me better understand him, if only through the depth of their conveyed grief. One, dated July 6, 1857, is addressed to “Governor Swain,” although Swain was by then more than twenty years removed from the office.

Gov. Swain,

My Dear Sir,

I have a most melancholy and unfortunate piece of information to communicate, and think it best to do it at once before rumor renders it more unpleasant, if that were possible, than the sad reality.

Our dear old friend Dr. Mitchell is no more. He is lost among the mountains and the utmost search we have been able to make has yet proved unavailing.

After navigating folders of papers conveying to me the life of Mitchell, I’m contented that I’ve come to know the outdoor adventurer as well as I can in the quiet spaces of a library. I spend the rest of the afternoon walking the campus, in the knowledge that at times I’m walking where the professor once trod.

Within a week of the trip to Chapel Hill, I’m back at Mount Mitchell, and I’m informed for the fourth time after inquiries to four different parties that Mitchell Falls is strictly off limits. I do ascertain from a park ranger the region of the falls, and an agreement that several thousand yards taken in its general direction does not constitute trespassing, especially if the ranger is not looking.

I walked out from the from the visitor center and down a gravel road, until I was quickly warned off the task by signage and the reluctance to land my helpful accomplice in serious trouble.

I then walked back to my car and after looking at maps, decided to head to Roan Mountain on the North Carolina—Tennessee border, where Mitchell visited in the 1830s, and a place of which he was especially fond for its ability to be reached by horseback.

En route I drove past a roadside marker to Andre Michaux, the French botanist who surveyed western North Carolina and its flora in the late 1790s. Through Michaux’s account of his findings, which Mitchell later read, he influenced the professor perhaps more than any other single factor to one day explore the region.

Finally, I arrived at Carver’s Gap, parked my truck, and meandered to the top of Round Bald, elevation 5,826 feet. Its stunning beauty caught me off guard, a 360-degree vista of blue mountains, calf-high wind-blown grasses, and blossoming patches of rhododendron. A light breeze and a fading sun perfected the setting with the life and color so absent from the black and white renderings of the stoic Mitchell I first encountered.

Perhaps now, and only now, I have gained some glimpse into Mitchell: a brilliant, flawed, persistent man who—at his core—fell in love with the mountains.