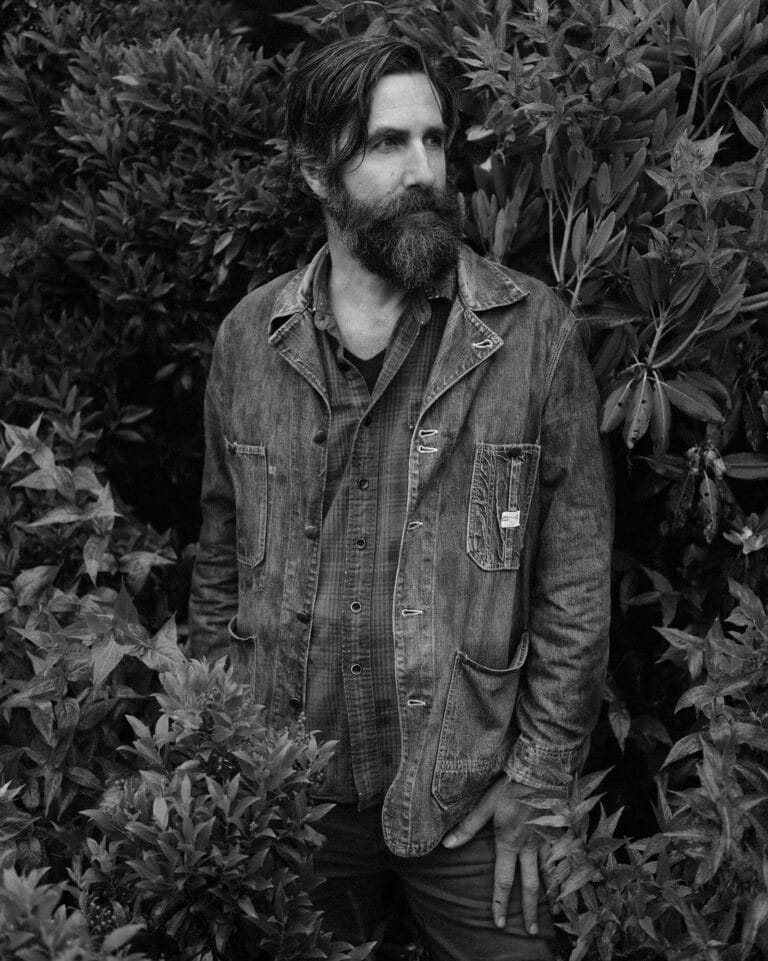

Jay Leutze teamed up with locals near Roan Mountain to stop a gravel quarry from destroying a scenic peak in Southern Appalachia. Photo courtesy of John Manuel

Author fights for his beloved Blue Ridge in a page-turning bestseller

Jay Erskine Leutze was living a simple life in the mountains of western North Carolina when he was drawn into a battle against the operators of a proposed gravel quarry very close to the Appalachian Trail (A.T.) in the Roan Highlands near his home. He chronicles the genesis of the fight and his subsequent four years in the state court system in the recently published Stand Up That Mountain: The Battle to Save One Small Community in the Wilderness along the Appalachian Trail. It integrates comprehensive legal details into a gripping storyline that includes a plethora of authentic characters, from colorful residents of the small mountain town to distinguished lawyers in Raleigh to dyed-in-the-wool environmental activists. In this era of environmental calamity everywhere we look, Stand Up That Mountain is a refreshing and optimistic perspective on the power of people to speak up for places they love. I spoke with Leutze the morning after he gave a public talk in Asheville for the celebration of the 75th anniversary of the A.T.

Give us an overview of what happens in the book.

The conflict surrounded a private mining enterprise that was forced to move from its current location, and they went looking for places to mine for gravel. They managed to get a permit to mine 151 acres including the summit of a 4,400 foot peak called Belview Mountain. One day, I got a telephone call from a very articulate woman who told me that the Mining Act of 1971 was being violated behind her house. She said she had photographs that she would share with me. So I went to meet her and that’s when I learned she was a 14-year-old girl named Ashley Cook. She was being homeschooled by her Aunt Ollie and her Uncle Curly in their home, which was a defunct auto-repair shop, a cinderblock building on the side of the road. She asked me to help her because she knew I had been to law school. I felt very drawn in by their passion and the fear that they had. What followed was a four-year legal battle between a private citizens group, and public interest law firms, and two national conservation organizations, the A.T. Conservancy and the National Parks Conservation Association.

How did you decide to write a book about your experience?

By the time we were filing the lawsuit, I knew I was living in a story that was rich with characters. I knew I was in the middle of a remarkable story with people who were confronted with conflicts, which is what makes stories move. Stories are powerful because they mimic our lives. My life had become a script for a hell of a movie. One of the joys of this story has been watching local people have an opportunity to stand up for the things they care the most about. This story is providing a lot of inspiration to people who see natural gas companies coming into their communities to do hydraulic fracturing and people who are facing threats in a nation with a growing population where we are bumping up against each other more and more.

What was the relationship like between the local community and the conservation organizations you were working with?

There was a lot of distrust in the local community of the A.T. community. The trail is placed in the most remote locations that can be found, so there’s almost no contact between hikers and these communities until the trail crosses a road. So Ollie and Ashley and Curly didn’t really have any realization that there was a National Park unit behind their house. Ollie called it “that little dirt path up on the hill.” So it took some convincing to build some trust.

What are you working on now?

I buy land for the Southern Appalachian HighlandsConservancy in Asheville. The landscape that my land trust was founded to protect was the Roan Highlands. A lot of people asked me if I was going to practice environmental law after this case. Instead, I started working with the land trust community, working with willing landowners who wanted to protect their own land and badly needed tools to do that. That’s what land trusts provide. The land trust movement has protected more land over the last six or seven years using voluntary conservation easements and land acquisition than land that was lost to sprawl. I wanted to be in the middle of that. One of our recent successes was partnering on the acquisition of the 10,000-acre Rocky Fork in East Tennessee.

What do you love about the Southern Appalachians?

I live in a very sparsely populated landscape where people are still getting lost. Several times a year on foggy days the word goes out that a small group of hikers is lost in the Roan. I think it’s amazing that in this fast-growing state that there are still places where reasonably competent outdoor enthusiasts can get lost. That inspires me. I love crossing a ridge and standing in a place where I’m quite confident that nobody has stood in a very long time, if ever. We can secure that experience for future generations, not only in a beautiful landscape, but in a landscape of remarkable biodiversity. A lot of my love is connected to fishing and clean water. I love drinking right out of my spring. I live at the top of my watershed, and so many people live downstream of me. We need to figure out a way to ensure that everybody’s got clean water.

Is there anyone you’ve turned to as a role model in your own work and life?

Mark Twain. I find something relevant in Twain every time I pick up his writing. Of course I love Wendell Berry, a lot of nature writers, a lot of southern writers too. But I pick up Twain first. He gets me in a framework of diabolical creativity.

Jay Leutze will be speaking about Stand Up That Mountain on February 25 at Lynchburg College.