John Dalen’s backyard is a backcountry skier’s paradise

The front end of the snowmobile is held together with duct tape, which isn’t surprising when you consider the machine is at least 20 years old. It was “gently used” when Shawn Hash originally bought it in the ‘80s when he was a cat skiing guide in Colorado. He and a ski buddy would take turns driving the machine to access the backcountry ski lines along Vail Pass. Two decades later and the gray beast is in West Virginia, gassed up and ready to take five of us to the base of Pharis Knob, a privately owned mountain adjacent to the Sinks of Gandy that has been cultivated into a backcountry ski paradise.

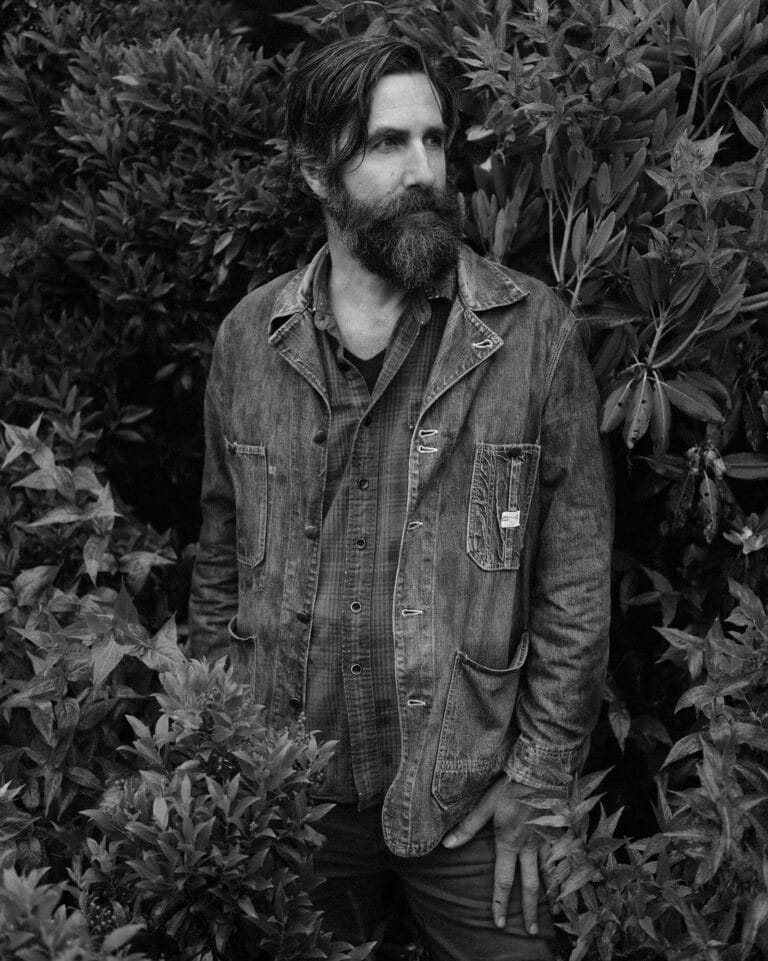

At least two feet of snow covers the road to the bottom of the mountain and more snow continues to fall as Hash revs the machine’s engine and slowly drives it off the bed of John Dalen’s massive blue diesel farm truck. Dalen owns Pharis Knob and much of the land surrounding it. He has 38 head of cattle on his farm outside of Franklin, W.Va. but makes most of his money from selective cuts on his properties scattered around Pendleton County. Farming and timber is what Dalen does. What Dalen is, is a backcountry skier. The 58-year-old family man has spent most of his adult life in pursuit of pristine backcountry stashes all over America. It’s simply a matter of serendipity that Dalen inherited what could arguably be the best backcountry ski destination in the entire Mid Atlantic.

Pharis, which peaks at 4,675 feet, sits a little southeast of the popular ski resorts in West Virginia’s Canaan Valley. The mountain has a broad north-facing hollow covered in hardwoods and spruce that acts as a bowl, catching Lake Effect snow storms coming from the northwest. High winds blow snow off the wide, flat mountain peak into the trees on the north side, creating deep veins of snow running through the trees. As a backcountry ski destination, Pharis has the golden trifecta of characteristics: an average of 160 inches of snow a year, 1,100 feet of consistent vertical drop at high elevation, and a north-facing slope. The skiable terrain on Pharis is 500 feet higher in elevation than any resort in operation in nearby Canaan Valley, and Dalen has complimented the natural attributes of his mountain by grooming half a dozen different runs on the north face into perfectly spaced downhill glades. He’s thinned the trees to allow more space for controlled turns, and removes debris and rocks from the runs during the off-season, so he can ski it with less of a base than most other backcountry spots.

Pharis, which peaks at 4,675 feet, sits a little southeast of the popular ski resorts in West Virginia’s Canaan Valley. The mountain has a broad north-facing hollow covered in hardwoods and spruce that acts as a bowl, catching Lake Effect snow storms coming from the northwest. High winds blow snow off the wide, flat mountain peak into the trees on the north side, creating deep veins of snow running through the trees. As a backcountry ski destination, Pharis has the golden trifecta of characteristics: an average of 160 inches of snow a year, 1,100 feet of consistent vertical drop at high elevation, and a north-facing slope. The skiable terrain on Pharis is 500 feet higher in elevation than any resort in operation in nearby Canaan Valley, and Dalen has complimented the natural attributes of his mountain by grooming half a dozen different runs on the north face into perfectly spaced downhill glades. He’s thinned the trees to allow more space for controlled turns, and removes debris and rocks from the runs during the off-season, so he can ski it with less of a base than most other backcountry spots.

So how good is the skiing on Pharis Knob? Hash and his two buddies (Steve and Jeff), all experienced backcountry skiers with years of ski bum life under their belts, spent six hours driving from Blacksburg, Virginia, to Pharis Knob, W.Va., in the midst of a snowstorm this morning. And that six hours of drive time just got them to the bottom of the mountain. From that point, they’ll take an hour to skin up the mountain on telemark and alpine touring gear. They’ll spend those eight hours just for the opportunity to ski Pharis’ backcountry lines for half a day. Then they’ll reverse the process, driving six hours home in the dark during the tail end of the same snowstorm. Twelve hours of snowy drive time for four hours of skiing, half of which is uphill. That’s how good Pharis Knob is.

“There’s no comparison to Pharis, at least around here,” says Hash, who’s spent years of his life searching for perfect backcountry ski lines. “You can probably find a similar mountain in New England, but in the Mid Atlantic, this is a unique situation. The perfect blend of terrain and conditions.”

Three months of potential snow remains in the season by the time I make it to Dalen’s farm house in Franklin, but he’s already declared it to be the best winter for skiing in more than 30 years. Most skiers in the Southeast would agree. By the end of the winter, Pharis will see an estimated 24 feet of snow, as much powder as many Western resorts.

I drink Budweisers with Dalen at his kitchen table the night before I get to ski Pharis. He talks to me about building his family’s timber-frame house himself, about the fluctuating prices of feed, about ice climbing and fly-fishing. He’s gray and weathered but also remarkably young, the way you are when you spend your life cutting timber, raising cattle and skiing through the elements. He shows me pictures of his father dressed in the iconic 10th Mountain Division snowsuits from World War II and we talk about the art of balancing work, family, and skiing.

“It can cause problems with my wife sometimes,” he says. “When the snow’s in, you have to drop everything to ski. You can’t not go. I used to be obsessed with it. I’m more laid back now.”

I can tell Dalen has a skewed sense of what it means to be laid-back. The man works almost around the clock for six months out of the year in order to devote as much time as possible to skiing during the winter, squeaking out every possible day on Pharis Knob. When the snow is in, he’ll wake before dawn, feed the cattle, then head straight to the mountain.

This is Dalen’s exact routine the day I ski with him. He’s up and done with his farm chores by the time Shawn Hash and his cohorts show up for the day. I ride with Dalen in his farm truck with no heat from Franklin to the road at the base of Pharis while Hash follows. We have the snowmobile, our skis, a shovel, chains, and an extra can of gas in the back of the truck. The state doesn’t plow the road to Pharis, so we drive the truck as far as we can through the snow, then we wrap chains around the tires and drive a little farther. Then we pull to the side, unload the snowmobile, and Shawn runs tow-in shuttles for the remaining two miles to the bottom of the mountain where a gate separates Dalen’s property from the road. From the gate, we hike and scrape up to Dalen’s cabin, a small, 10-by-12-foot warming hut with a wood stove, couch, sleeping loft, and a bottle of Vladimir vodka chilling on the table.

Hash starts a fire in the stove while Dalen and Steve trade stories about multi-day ski trips in Yellowstone and the Wind River Range. They’re all planning on spending a couple of nights in this cabin at some point this winter, but today, it’s strictly an in and out mission. Ski as much as possible before the sun sets, then head our separate ways.

The snow continues to dump as we start the long skin up the mountain. I’m carrying my downhill gear on my back and wearing snowshoes on my feet. There’s so much snow on the ground, even with the snowshoes, I sink to my knees in powder with every step. Occasionally, I lose my balance and fall, my pole sinking in snow all the way to the handle. It’s as if the entire side of the mountain is covered in one deep drift.

At one point, I ask Dalen if anyone else has ever booted up Pharis with their downhill skis strapped to their back. “One other guy.” He waits a beat. “He had a stroke a week later.”

We climb for maybe two miles along a skinny forest road that switchbacks up the slope. The mountain has about 20 miles of primitive forest road and singletrack, which would be ideal for mountain biking and hiking during the summer and fall.

We discuss the potential of turning the mountain into a four-season adventure resort, with guided backcountry ski trips during the winter, and mountain biking, hunting, and fishing through the rest of the year, but it’s obvious Dalen has reservations. Access during the winter would certainly be an issue. Without plowed roads, just getting to Pharis becomes an adventure. But Dalen has reservations beyond the logistical difficulties of turning Pharis into a commercial entity. Pharis has been in his family since just after the Civil War. His great, great uncle was a Confederate soldier who was captured and held in the western flatland of West Virginia. When he was released, he had to walk across the Sinks of Gandy to get home. When he crossed Pharis and the surrounding valleys, he fell in love with the area. Before he volunteered for the war, he asked his slave, Jake, to take care of one of his pieces of property and treat it like his own. Jake agreed. West Virginia was a land torn by the war. Banditry was common. Raids and horse thieves plagued local farmers. Union sympathizers raided Confederate farms and vice versa. Jake protected the farm from raiders so it was one of the few properties that was still intact and in working order after the war, leaving Dalen’s great uncle in solid financial shape. He began buying other farms in tax sales, letting the original owners stay on as tenants, then willing many of the pieces back to the original families after his death. Pharis, which was named after the original owners, was one of the farms that Dalen’s great uncle kept to pass on to his own family.

Listen to Dalen tell stories about his ancestors, his father, even the trees he’s cut from the mountain side, and you get the feeling the land is his strongest connection to his family. He takes pride in both his land and family. The two are intertwined, as if you can’t have one without the other. He’s more than generous when it comes to friends accessing the mountain, but turning it into a commercial business is a different monster altogether. Imagine the prospect of turning the thing you love most into a business.

When we reach the top of the mountain, I’m three hours into the trip and I haven’t turned my skis downhill yet. The four wheel drive truck-snowmobile-skin up process is something most backcountry skiers are used to, but it tends to keep the masses from truly falling in love with this niche sport.

“What it takes to get to a place to ski it is part of the fun,” Dalen says as Hash and Jeff lock in their bindings for the downhill ahead of us. “Out West, some of the best spots can take two days of touring and climbing to reach. The notion of isolation is part of the appeal.”

The group is sweating but smiling as we stand at the top of Pharis looking at the first downhill run of the day. Dalen has gladed four runs of about 1,100 vertical feet each. They all funnel into the same point that leads back to the cabin. The trees are perfectly spaced in the run before us, but the first 500 feet of drop is black diamond steep. The grade eventually mellows out when the slope hits the road, but this first stretch is intimidating. Hash tells the story of how he brought two other guys up to the mountain on a powder day a few years ago. They spent the better part of the day working to get to the top of Pharis, just like we did today, but once they reached the top of the mountain, the two men took one look at the steep terrain below them, removed their skis and walked back down. They said it was too steep to ski.

Dalen skis the fresh powder first and the rest of us watch as he executes a series of wide, flawless telemark turns, genuflecting all the way to the road. He leaves perfect “S’s” in the snow behind him. Hash goes next, then Steve, then Jeff. They all sink knee deep into the snow at the beginning of their turns, then pop out to the lip of the snow at the end. Sink and pop, sink and pop. It looks effortless, like they’re bouncing on a trampoline hidden beneath the powder.

My turns are nowhere near as graceful. Skiing powder requires considerably more effort than skiing a groomed run. It’s been too long since I’ve skied powder and my timing is off. Halfway down the slope, instead of springing out of one of my turns, I sink deeper into it and eat it, flying head first into the powder. For a few seconds, the world turns completely white as I’m completely immersed in soft, pillowy snow. You hear stories about skiers actually drowning in too much snow out West, but you don’t think it’s possible on the East Coast. On Pharis, it seems, drowning in snow is possible. I pop out of my white cloud and immediately cough up a lungful of soft, light powder. It burns, so I cough more as I gingerly make my way down the remainder of the run, rejoining Dalen and the others at the road.

It would be easy to feel completely deflated. To spend several hours and thousands of calories just to reach the top of a mountain, then fail miserably doing the very thing you worked so hard to be able to do, could be frustrating. But somehow, I’m okay with it. There are more runs ahead of us–the plan is to run laps on each of Dalen’s groomed glades until it gets dark–so there will be more time to succeed or fail. But honestly, I’m more possessed with the notion of witnessing Pharis, on this day, than I am about skiing Pharis. There is three feet of snow everywhere you point your skis. There’s a fire and bottle of vodka waiting in the warming hut. There are new ski partners to get to know, new powder stashes to find. The joy I find on Pharis isn’t about the skiing, it’s about experiencing the moment. This happy moment in time, where ideal conditions meet the ideal mountain. •