Quintessential Blue Ridge musician Larry Keel on how the pandemic has given him perspective—and a startling wellspring of inspiration.

Larry Keel sits in a lawn chair atop a grassy hill on the backside of his Lexington, Virginia, farm fingerpicking a banjo. The 51-year-old is barefooted, wearing jeans, a faded polo shirt (purple) and a “Virginia is for Lovers” trucker’s cap over a bushy white beard and black mustache. The tune morphs from a funky take on the bluegrass standard “Nine Pound Hammer” to a lilting and emotive roll. A gentle sadness washes over the mountain landscape. Fields and forests shiver in the early-June breeze; the cloud-filled sky seems to richen in color, to huddle a bit closer to the ground.

If one were not aware of Keel as the reigning heavyweight champion of fast-fingered acoustic guitar, they might well mistake him for some backwoods banjo sorcerer. “Whoops,” cries Keel, dropping the tune and flashing a prankster grin. In a gravelly, exaggerated drawl, he says: “I won’t supposed to show you that!”

The as-of-yet untitled song is one of 10 original pieces composed by Keel since he started quarantining with his wife, Jenny, in mid-March. He recently began arranging and recording them in his home studio for a solo album due on September 1. Though currently nameless, Keel calls the record “thematic.” For him, the quarantine has been an unexpectedly welcome pause: This is the longest he and Jenny have spent in one place for more than 25 years. Slowing down has brought reflection.

“I’ve been looking back on my musical life, my career, thinking about all the different twists and turns, and how far I’ve come,” says Keel. One emotion is overriding: Gratitude.

“I just feel so, so grateful to the heroes I looked up to and learned from—they helped me find my path; it’s because of them I’ve gotten to live a life filled with so much beauty and so many amazing experiences,” says Keel. But now that gratitude has expanded to include “getting to see the younger generation come into their own and take up the mantel.”

Keel describes the album as a kind of musical summation before entering the next phase of his career. On one hand, it pays tribute to old vanguard stars like Tony Rice, Doc Watson, Norman Blake, David Grisman, Peter Rowan, and Vassar Clements. On the other, it’s a tacit acceptance of his role as the new elder statesman of bluegrass-based progressive acoustic music—Keel is cited as a major influence by many musicians from Andy Falco of the Infamous Stringdusters, to Yonder Mountain String Band’s Adam Aijala, to 27-year-old guitar phenom Billy Strings.

Invoking Jerry Garcia’s solo project, “Garcia,” Keel hopes to create a musical self-portrait centered around the master ideas that established his sonic trajectory and will, eventually, define his artistic legacy. To do it, like Garcia, he’ll essentially play every instrument on every song. Keel says the approach is producing the most vulnerable and intimate recordings of his career.

“This is a very special project for me,” he says, likening the album to a being that’s been gestating inside of him for 40-plus years. But he can’t just give birth to it all at once. “In my mind, I hear [all the instruments] together,” says Keel. “I’m having to isolate individual parts and pull them out of that world of imagination into this world of things and stuff.”

That makes the process more challenging, more interesting. But for Keel, the territory is familiar: The descriptors have long defined his approach to music. Though reared on traditional bluegrass guitar since age seven by his father and older brother, Gary, teenaged Keel became enamored with electric six-string icons like Clapton, Hendrix, and Robin Trower. Discovering boundary-shattering bands like New Grass Revival, Old and in the Way, and the Tony Rice Acoustic Unit was life altering. “Those groups introduced me to a whole new realm of possibilities,” says Keel. “They were pioneers, blazing trails to places I’d yet to figure out I wanted to go.”

Keel became a fixture of the Southeastern bluegrass scene, attending festivals and winning numerous competitions. By 1990, he’d joined forces with other young, Virginia-based envelope-pushing prodigies—namely Will Lee, Danny Knicely, and Mark Vann, who went on to help found Leftover Salmon. Three years later, Keel won the infamous guitar competition at Colorado’s Telluride Bluegrass Festival. In 1994, his group, Magraw Gap, took first prize as a band.

The success catapulted Keel into the limelight. He was soon being ushered onstage alongside heroes like Rice, Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Bela Fleck and others. His passion for experimentation led to countless collaborations, including the Billboard chart-topping album, “Thief,” recorded in 2010 with jam-band mainstay Keller Williams.

Keel calls the album-in-progress a tribute to those days of ascendancy. In it, he seeks to capture the awestruck wonder of experiencing his wildest boyhood fantasies come true. But, as with the poet William Wordsworth’s “Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey,” the remembrance issues from the clear-eyed vantage of a mature adult that has, through dogged persistence and decades of effort, attained the pinnacle of artistic achievement.

“This has been a very different process from how I normally go about making a record,” says Keel. In the past, songs have been gathered through the years amid relentless touring. Spending months at a time mulling over one project was unthinkable. Hence the novelty of the pandemic-related pause.

It’s given Keel the freedom to let compositions develop organically. When an impasse presents itself, he picks weeds in his vegetable garden, takes a hike in the woods, or goes fly-fishing in nearby trout streams.

“These Blue Ridge Mountains are what gave birth to this music in the first place,” says Keel. The album—and his sound in general—owes as much to them as its human progenitors. “If I get stuck, I try to clear out my mind and let the spirit of the land work its way into my subconscious and steer things in the right direction.”

Describing the process and its results, Keel sometimes uses the word ‘spiritual.’ But while he embraces the supernatural, he does so with a wily down-to-earthness. Take, for example, momentary possessions by the late fiddle guru Vassar Clements.

“When you play with somebody like Vassar, you take on some of their energy,” says Keel. When they pass, “it’s like an anchor that lets their ghost visit and pick a few lines with you now and then. For instance, I could be deep in a jam and have a Vassar lick come out of nowhere. Well, that tells me we’re on the right track: We’ve got so hot the old rascal wants to get a piece of the action!”

Similarly, Keel says the album is, in part, the by-product of an eye trained on the future. Looking ahead to the next 25 years, he’s determined to blaze as many paths into the musical unknown as possible.

“I play with a guy like Billy Strings and it fills my heart with so much joy to hear him do his thing with one of my ideas,” says Keel. “To me, that’s the greatest compliment. That tells me I’m doing my part to ensure this music that’s filled my life with so much love and happiness will live on for generations to come.”

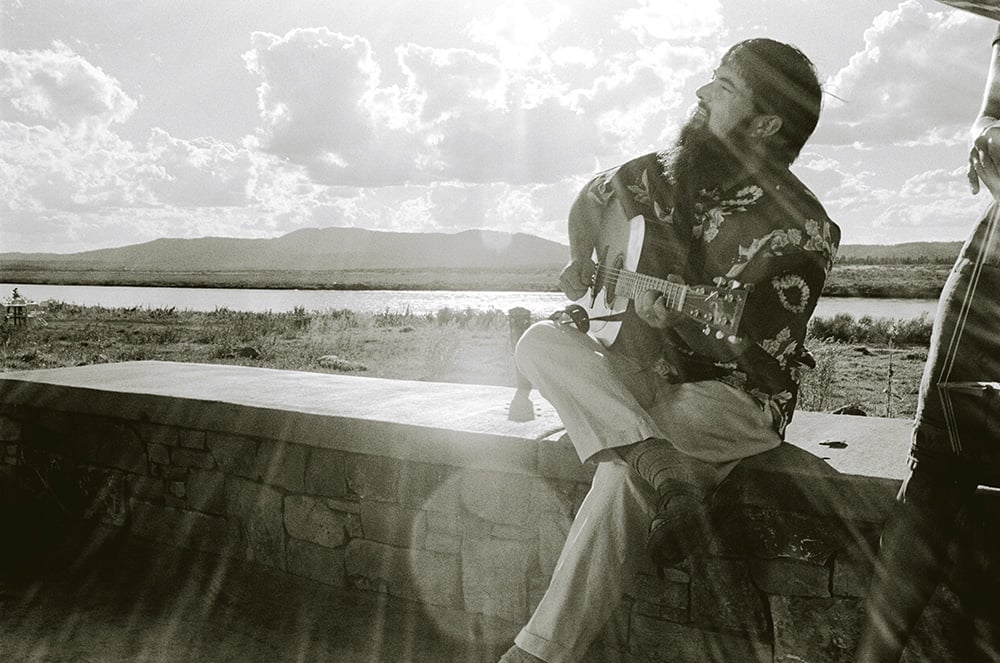

Photo by C. Taylor Crothers