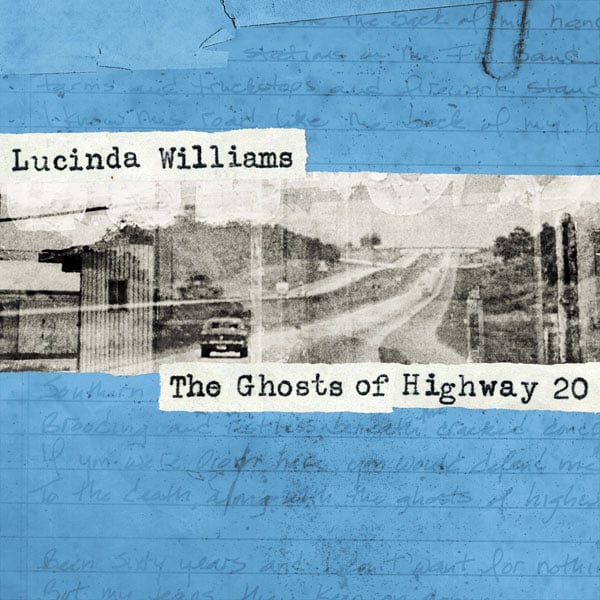

Unlike most artists who take a career towards the four-decade realm, Lucinda Williams has managed to become more prolific with age. In the fall of 2014, Williams, 62, released the deeply insightful double album, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, so it was surprising when, just 17 months later, she unveiled another sprawling set of tunes in the new The Ghost of Highway 20. For Williams, her twelfth studio album is a 14-track road trip down memory lane, as she channels her experiences growing up in the South into a collection of heartache-laced, exploratory alt-country tunes.

Williams is a native of Lake Charles, Louisiana, but during childhood she moved around a lot and lived in many neighboring Southern states. A common thread was Interstate 20, a 1,500-mile stretch of American highway that runs between South Carolina and Texas and along the way passes many simple landmarks that can shape a keen artist’s formative years. In her trademark voice, quavering, at times to the point of almost sounding slurred, yet always extremely emotive, Williams sings in the title track, “Farms and truck stops, firework stands; I know this road like the back of my hand.”

As the song continues she reveals these recollections aren’t always fond: “Been 60 years, I don’t want for nothing; But my tears, they keep on coming.”

Williams has never shied away from telling her listeners she’s hurting. At times her revelations are straightforward, while others are poetically cryptic, even when she’s singing in the first person. The latter likely comes from her father, the late poet laureate Miller Williams, who died on New Year’s Day, 2015, and is remembered throughout his daughter’s new album. Williams adapted the meandering, ethereal opener, “Dust,” from one of Miller’s poems, and a few songs later she grieves loss and ponders the afterlife in the back-to-back combination of the haunting ballad “Death Came” and the twangy blues tune “Doors of Heaven.”

When Williams was growing up, her father worked as a visiting professor at different colleges. She lived in different cities when first pursuing her music career, too; first trying Austin, then Los Angeles, before finally settling in Nashville. Williams’ first album, 1979’s Ramblin’, was a collection of old blues and country tunes, but critical recognition didn’t come until nearly a decade later with 1988’s Lucinda Williams, an album that was released on the London-based independent label Rough Trade Records.

At the time she was having trouble finding a scene. This was two years before Jeff Tweedy and Jay Farrar released Uncle Tupelo’s debut album No Depression, which essentially birthed alt-country as a sub-genre, and obviously long before Americana became the category applied to artists who put various styles of American roots music in a blender. At first, Williams was told she was too country for rock and too rock for country, but sticking to her guns has served her well, especially in the current musical climate where genre blurring is not only accepted but expected.

Williams is now considered a trailblazer, and her aforementioned self-titled record, which recently received a 25th anniversary reissue, has proven to be a statement ahead of its time. The album contained “Passionate Kisses,” a song that eventually won Williams her first Grammy for Best Country Song for the version released by Mary Chapin Carpenter in 1992. She didn’t receive her due as a performer until the 1998 release of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, an album that mixed the influences of Williams’ Southern roots with tight modern-rock arrangements and featured contributions from Emmylou Harris and Steve Earle. The album went Gold, notched a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album, and essentially made Williams the household name in roots music that she is today.

Ever since, Williams has released albums every few years. She hit a blue period that peaked with 2007’s West, which lamented bad romance and the loss of her mother, and at times was too depressing for comfort. She then turned a corner towards optimism with Blessed in 2011, which followed her marriage to manager Tom Overby.

Lately, though, Williams has found a new creative stride. With Ghost being her second double album in less than two years, her pen is clearly flowing, but the record also has distinguishably fresh sonic open-mindedness. On all but two tracks, Williams’ steadfast backing band is augmented by jazz guitarist Bill Frissell, whose experimental flourishes add an emotional intensity to Williams’ slow-burning recollections. That’s especially true during the desolately atmospheric reading of Bruce Springsteen’s thematically relevant “Factory,” as well as the patient acoustic strummer “Louisiana Story,” which unfolds for over nine minutes like a passed-down front-porch tale. The closing “Faith and Grace” is even longer, clocking in at nearly 13 minutes as Williams exorcises demons with possessed fervor while encompassed in Frissell’s spacey licks. It’s a riveting, psychedelic Bayou-gospel journey, and like the entire album, one of Williams’ best examples of music as cathartic release.

[divider]more from the trail mix blog[/divider]